Tracking the Prince: Rock of Cashel

/Part 2 in a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. See Part 1.

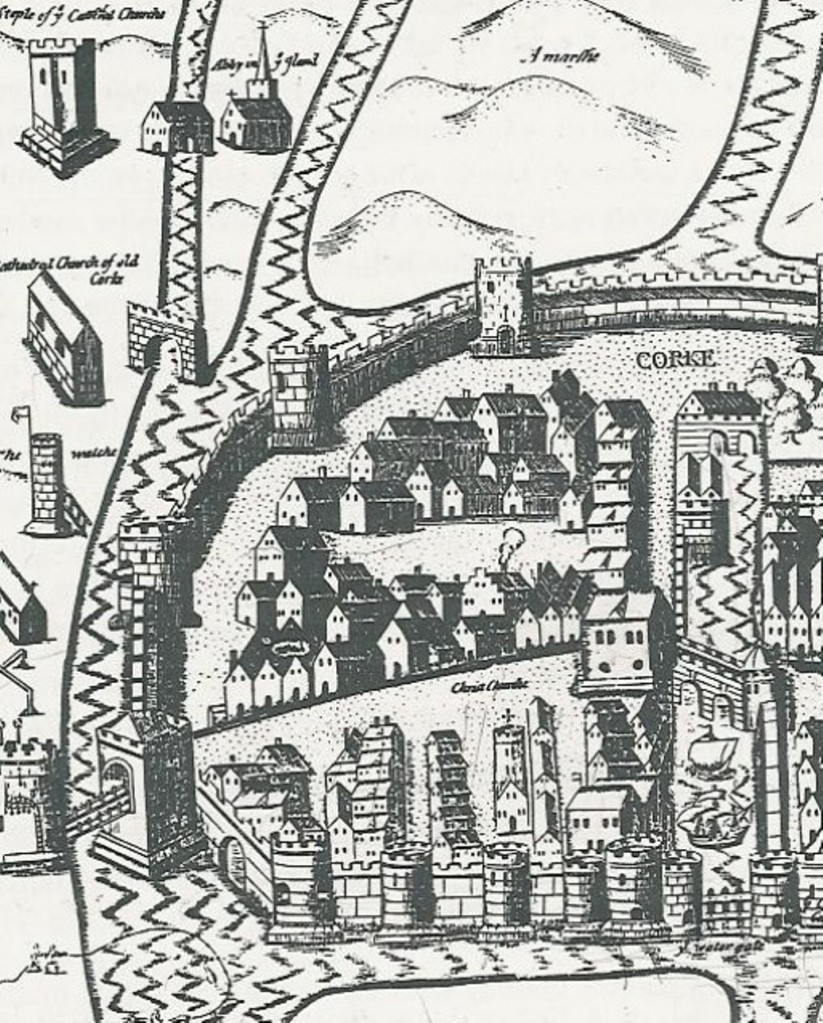

After a cup of tea and a lemon bar in Kanturk, I proceeded east on the N72/N8 to the town of Cashel (from the Gaelic caiseal meaning stone fort), in County Tipperary. I’d been to Cashel with my family when I was 14 years old, to see the great Rock of Cashel: “a maze of architectural ruins spanning many centuries” according to the Irish Cultural Society.

After a cup of tea and a lemon bar in Kanturk, I proceeded east on the N72/N8 to the town of Cashel (from the Gaelic caiseal meaning stone fort), in County Tipperary. I’d been to Cashel with my family when I was 14 years old, to see the great Rock of Cashel: “a maze of architectural ruins spanning many centuries” according to the Irish Cultural Society.

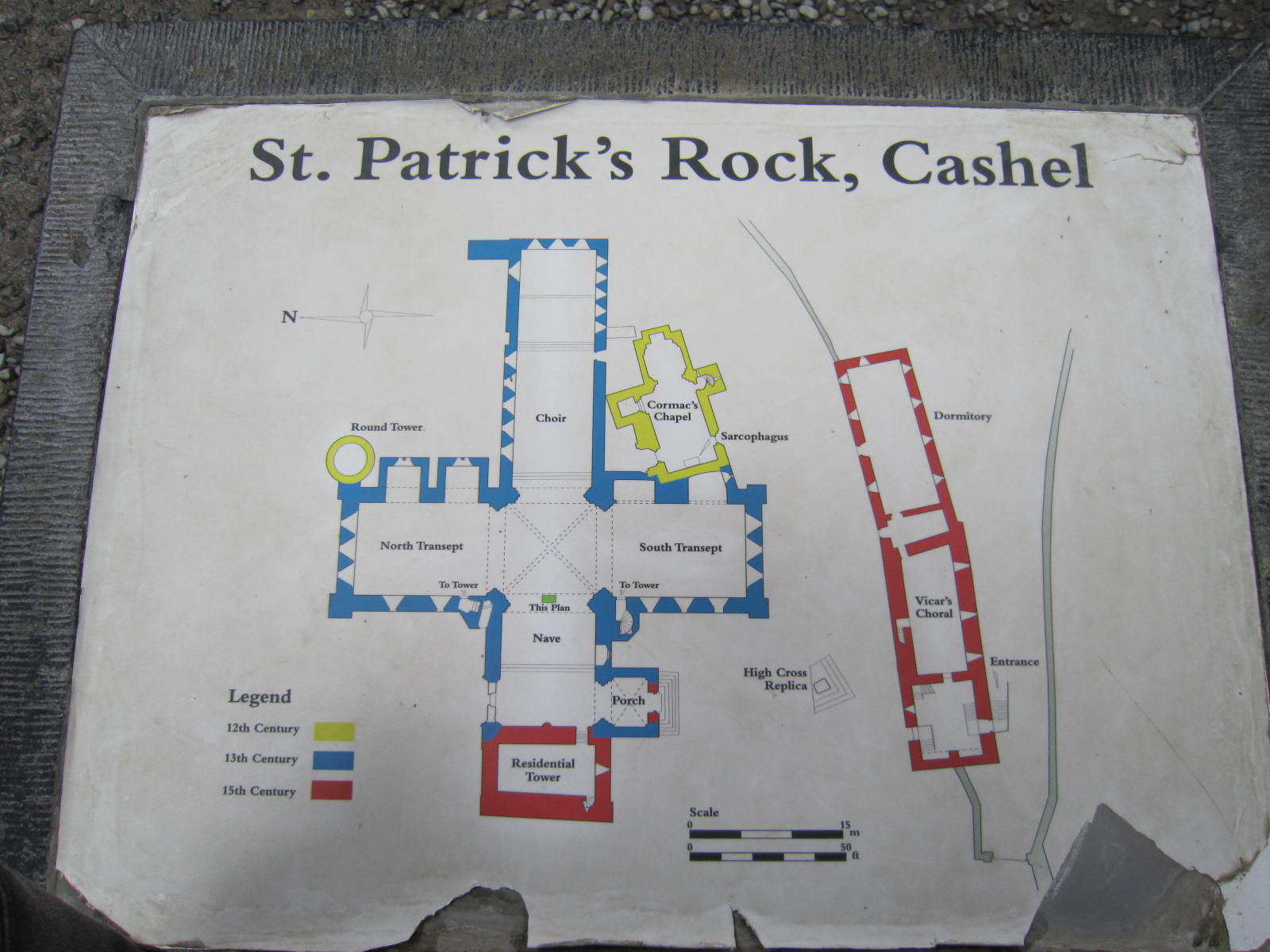

I remembered little about this historical site except that the great cathedral was enormous, the structures intimidating, and all built on a rock promontory rising more than 300 feet high to overlook miles of lands that surrounded it. Impressive story, yes, and unforgettable architecture, to be sure, but now I needed specifics about its history, its layout and many more details.

Centrally located in the southern half of Ireland, legend has it that the promontory was created when the Devil took a bite out of a nearby mountain and the great chunk of rock fell from his mouth. Structures at this location date back to the fourth century, and later the Rock of Cashel became the seat of the Munster kings, including Brian Boru who in the 10th century unified all of Ireland under his rule—until 1014 when Vikings killed his son and him at Clontarf.

The round tower, built in 1101, was designed for protection from Vikings, with its door 12 feet off the ground and a ladder that could be pulled inside in case of attack. Cormac’s tiny chapel was started in 1127.

In the late 13th century, the site was deeded to the Catholic Church, and Saint Patrick’s Cathedral was built on the foundation of an older one. After King Henry VIII split from the Catholic Church and established the Church of England, he appointed his own bishops, as did his daughter Queen Elizabeth in later years.

“In the wind swept silence one can feel the spirit of the ancient chieftains, kings and bishops of Ireland who once lived and worked here.” --James Conroy

After the English civil war when Parliament emerged victorious and King Charles I was beheaded, Oliver Cromwell brought his army to Ireland to crush the Irish rebellion once and for all. Starting in Drogheda in 1649, his march was brutal and bloody, and the cruelty of it remains controversial even today. Cashel was one of several villages sacked by Cromwell’s troops. When Catholic soldiers and town’s people sought refuge in the cathedral, Cromwell recognized no sanctuary, ordered his troops to pile turf around the cathedral and set it afire, killing all within.

Across the courtyard from the cathedral is the vicar’s choral, including kitchen and dining hall for the men who assisted with cathedral services. This has been restored to serve as a museum. The dining hall is quite beautiful with dark ceiling beams, leaded windows and window seats, trestle table and tapestry. This choral became the setting for the mid-point scene in The Prince of Glencurragh, when the earls of Clanricarde, Ormonde and Cork come together to meet with the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Wentworth, who quickly takes control. Where the roof joins the walls, the decorative under-purlins are carved angels who look down on all below, and whose facial expressions add their own silent commentary.

Across the courtyard from the cathedral is the vicar’s choral, including kitchen and dining hall for the men who assisted with cathedral services. This has been restored to serve as a museum. The dining hall is quite beautiful with dark ceiling beams, leaded windows and window seats, trestle table and tapestry. This choral became the setting for the mid-point scene in The Prince of Glencurragh, when the earls of Clanricarde, Ormonde and Cork come together to meet with the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Wentworth, who quickly takes control. Where the roof joins the walls, the decorative under-purlins are carved angels who look down on all below, and whose facial expressions add their own silent commentary.

In the mid 18th century the Archbishop had the cathedral’s roof removed. Its lead content was considered valuable in that it could be used for ammunition, and alchemists of the time believed it possibly could be transformed into gold if the right process or catalyst was applied, because both gold and lead have similar properties. That controversial move left the site useful only as a tourist attraction. As this, however, the site is quite successful. Cashel is one of the top three centers of Irish culture.

For beautiful architecture, you may also want to visit the Dominican Friary tucked on the backstreets of the town of Cashel.

And a side note: While in Cashel I tried to visit Bothán Scór, a peasant cottage known locally as “Hanley’s,” that traces its history back to 1623. I hoped to see an accurate example of cottage life from that time. The tiny thatch-roofed cottage had a single window but it was blocked, preventing my view inside. You can see the cottage from the street, but according to the tourist office only one man has a key to the door, and they were unable to find him before I had to leave the town. This was the first of a few unfortunate missed opportunities during my travels. If you go and are able to see it, please tell me about it!

And a side note: While in Cashel I tried to visit Bothán Scór, a peasant cottage known locally as “Hanley’s,” that traces its history back to 1623. I hoped to see an accurate example of cottage life from that time. The tiny thatch-roofed cottage had a single window but it was blocked, preventing my view inside. You can see the cottage from the street, but according to the tourist office only one man has a key to the door, and they were unable to find him before I had to leave the town. This was the first of a few unfortunate missed opportunities during my travels. If you go and are able to see it, please tell me about it!

Thanks to The Irish Cultural Society of the Garden City Area; the Heritage and Tourist Office; Wikipedia; no thanks to the car park for Bailey’s Hotel!

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

See all my books and sign up for the newsletter here.

To me, the remarkable thing about this enormous and beautiful fortified manor house, and why I felt compelled to see it, is that it was the envy of all who saw it during construction, and yet it was never completed.

To me, the remarkable thing about this enormous and beautiful fortified manor house, and why I felt compelled to see it, is that it was the envy of all who saw it during construction, and yet it was never completed. (For a very detailed account of the castle with far better photos than mine, please see

(For a very detailed account of the castle with far better photos than mine, please see

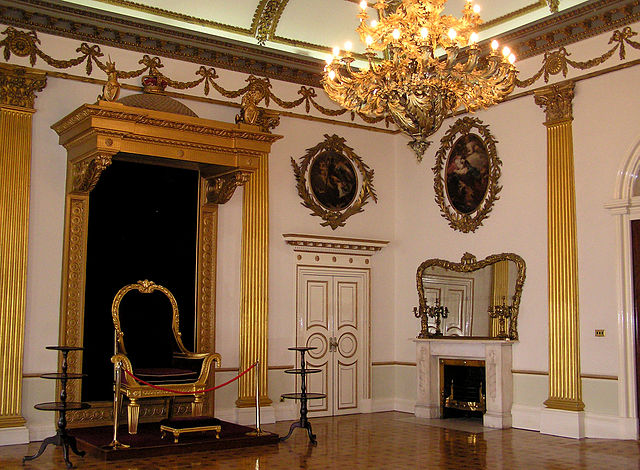

Now I wish I’d had a better head on me, for the castle will be the primary setting for my next book. Research already had begun last month when my sister unearthed this picture of me on the throne. Is it any wonder that I’m drawn to Irish history as much as I’m drawn to write?

Now I wish I’d had a better head on me, for the castle will be the primary setting for my next book. Research already had begun last month when my sister unearthed this picture of me on the throne. Is it any wonder that I’m drawn to Irish history as much as I’m drawn to write?

Embark on an adventure in Irish history -- 17th century, that is, with

Embark on an adventure in Irish history -- 17th century, that is, with