Enemies and Kings

/How history repeats in the comparison between Thomas Cromwell and Thomas Wentworth

Read MoreInternational Award-Winning Author

How history repeats in the comparison between Thomas Cromwell and Thomas Wentworth

Read MoreDivided by a gentle curve in the great River Boyne, the town of Drogheda in County Louth is one of the oldest and largest in Ireland.

Read MoreCharles II valued many things, including art, architecture, ships and science, but above all he had “an absolute commitment to his own survival.”

Read More

Today I begin a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. This book takes place in mid-17th century Ireland, when castle towers are losing their significance and the order of the day for the rich and powerful is a grand, fortified manor house that demonstrates their wealth and importance. I had mapped out 15 locations prior to my trip, so the series will cover each of these. Readers of The Prince can follow along using the map included in the book. I ended up using nearly all of the locations in some way, whether as an actual location for a scene in the story, or to inform something else.

Kanturk Castle was my first stop after arriving in Shannon. The structure inspired my vision for Castle Glencurragh, a fictitious castle near Skibbereen, County Cork, which is the dream and ambition of the protagonist.

Kanturk Castle was my first stop after arriving in Shannon. The structure inspired my vision for Castle Glencurragh, a fictitious castle near Skibbereen, County Cork, which is the dream and ambition of the protagonist.

Kanturk Castle is situated in north County Cork, just off the N72 about nine miles west of Mallow, along the Dalua river, a tributary of the Blackwater. It is named for the nearby market village Kanturk that existed centuries before the castle. While the name sounds exotic and mysterious, it actually means “the boar’s head” (from the Gaelic Ceann Tuirc).

To me, the remarkable thing about this enormous and beautiful fortified manor house, and why I felt compelled to see it, is that it was the envy of all who saw it during construction, and yet it was never completed.

To me, the remarkable thing about this enormous and beautiful fortified manor house, and why I felt compelled to see it, is that it was the envy of all who saw it during construction, and yet it was never completed.

Built by Dermot McDonagh MacCarthy starting around 1609, it is rectangular with corner towers standing five stories high. It is filled with magnificent fireplaces on each floor, large mullioned windows, arched doorways and a striking main entrance with Ionic columns on each side.

(For a very detailed account of the castle with far better photos than mine, please see The Irish Aesthete.)

(For a very detailed account of the castle with far better photos than mine, please see The Irish Aesthete.)

One legend about the castle is that all the stonemasons happened to be named John, and so originally the castle was known as Carrig-na-Shane-Saor (the Rock of John the Mason). Another story I came across was that during construction, MacCarthy needed free labor, so he and his men snagged travelers passing by, put them to work as slaves, and would not release them until they had worked on the castle for a year.

Why the castle was never completed remains something of a mystery. Some accounts claim that English settlers were concerned that the size and fortification of the castle signaled more rebellion from the Irish, and the Privy Council of England halted construction. MacCarthy was so incensed, he had the blue tiles on the castle roof torn away and thrown into a stream. Other accounts hold that MacCarthy simply ran out of money to continue.

When MacCarthy’s son, Dermot Oge, succeeded him, Kanturk and the lands around it were heavily mortgaged. Dermot and his own son were killed during a Cromwellian battle in 1652, and at the end of the confederate war Kanturk Manor was awarded to Sir Phillip Perceval, an English Protestant. Sir Phillip’s descendant, Sir John Perceval, was a successful parliamentarian, named Baron of Burton, County Cork, in 1715, Viscount Perceval of Kanturk in 1722, and Earl of Egmont in 1733.

And this brings me to a very personal connection to the story.

In 1932, Kanturk was donated to the National Trust by Lucy, Countess of Egmont, the widow of the 7th Earl of Egmont who was killed in a car crash in England. Her conditions were that the castle be kept as a ruin, as it was at time of hand-over. It is designated as a national monument.

When I visited, I saw a lovely, well-kept place where the locals walk their dogs, just as I often walk my dogs along a beautiful street with a beautiful name: Countess of Egmont—on an island more than 4,000 miles away.

It turns out that Sir John Perceval, the 5th Baronet of Kanturk and the 2nd Earl of Egmont, obtained a king's grant for properties in northeast Florida during a brief period around the 1770s, when Spain ceded the lands to Britain in an exchange for lands elsewhere. Amelia Island was then called Egmont Island, where the Earl and Lady Egmont owned a large indigo plantation. The island was later renamed Amelia in honor of the daughter of King George II of England.

The portrait: Catherine Perceval (née Compton), Countess of Egmont; with Charles George Perceval, 2nd Baron Arden; by James Macardell, after Thomas Hudson, mezzotint, published 1765, NPG D2382

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/

Rife with conflict, disaster, invention and sweeping change, there is not a century in history more fascinating and remarkable than the 17th. In the words of J.P. Sommerville, University of Wisconsin history professor, the 17th century is “probably the most important century in the making of the modern world. It was during the 1600s that Galileo and Newton founded modern science; that Descartes began modern philosophy; that Hugo Grotius initiated international law; and that Thomas Hobbes and John Locke started modern political theory.”

At the same time, the century produced an unprecedented synergy of disaster, as described by Robert Burton in 1638: “War, plagues, fires, inundations, thefts, murders, massacres, meteors, spectrums, prodigies, apparitions…and such like, which these tempestuous times affoord…” And all of that during the first few decades.

Some historians believe the changes and difficulties of this century resulted in part from a global climate change. The “Little Ice Age,” extending from the 16th to 19th centuries, delivered a particularly cold interval in the mid-17th century.

England in the 1630s recorded great floods, widespread harvest failure, intense cold winters, wet and cold springs, and drought in summer so excessive that “the land and trees are despoiled of their verdure, as if it were a most severe winter.” Such conditions would have been seen in Ireland as well.

These natural forces so affected human activity as to upset the existing social, economic and political equilibrium. People facing cold, famine, and grave uncertainty are likely to behave in more desperate manner.

Ireland in particular faced considerable unrest as the lands, traditional clans and centuries-old way of life were forever altered.

Life in Ireland

In 1603, Queen Elizabeth I died, leaving her throne and kingdom to James I. Her military forces in Ireland had delivered a crushing blow to end the Desmond rebellion in the southwest province of Munster.

The English saw Ireland as underutilized and ripe for exploitation. They sought to improve on Irish farming methods by settling their own more efficient farmers, and thereby increasing crown revenues.

The Earl of Desmond was among the Irish gentry who held castles, manor houses and vast tracts of land. They were mostly of Norman or Saxon roots, descending from distinguished families or clans who had obtained grants from Henry II in the 12th century. They resented the crown’s efforts to take control of their long-held dominions and displace their Irish tenants: typically subsistence farmers who paid rents either in food or in coin from the goods they sold. Often these tenants lived in one-room houses constructed of mud and grass, with no windows and a single door that served as both the entry and chimney.

Lord Deputy Arthur Grey seemed to defeat Queen Elizabeth’s purpose with his cruelty and scorched earth tactics. He left the province devastated, little more than a wasteland that would require years to recover, and was later removed from his position for excessive brutality—but, he had cleared the way once and for all for English settlement.

In a land already compromised by drought, the remaining Irish faced terrible famine, plague, disease, homelessness and oppression. Lands that had been owned and passed down through generations by traditional clans, especially Irish Catholic, were confiscated and granted to English military officers as reward for their service. Survival for the Irish was tenuous and choices were few. Some restoration took place in the coming years, but a fury simmered below the obedient surface.

In 1625, Charles I succeeded his father and extended his policies, filling his treasury through increased taxation and monopolies to his favorites, and expanding plantation in Ulster. When civil war erupted in England, Irish clans welcomed the distraction. They organized and rebelled again, retaking confiscated lands and ousting the English settlers, often violently.

When Parliament was victorious in the civil war, it took control of England and all of its business, and shocked the monarchies of the world by executing King Charles in 1649.

Parliamentary army leader Oliver Cromwell now turned his attention to Ireland, cutting an unrelenting swath of brutality, destruction and death across the island. Towns were leveled, people massacred, and terror wrought with full force. One estimate claims 618,000 Irish deaths from fighting or disease—an astounding 41 percent of the pre-war population.

Surviving Irish were relocated to rocky hills that served better for grazing sheep than growing crops. Some joined armies and fought in foreign wars; some became pirates. Some were sent to workhouses where they likely died; some escaped to colonies in America. Cromwell deported many to the West Indies where they perished from slave labor and tropical disease.

Irish Catholics were forced out of the Irish Parliament, while Catholic Mass and the Irish language were outlawed. Catholics were banned from holding office, Catholic clergy were expelled from the country, and Catholic landowners were stripped of their properties. An estimated one-third of the Irish-Catholic population was killed or deported.

On the heels of this work, Cromwell was elevated to “Lord Protector,” England’s uncrowned king, and he established his famed Commonwealth. Oppression of Ireland was severe and would be seen by historians as genocide. But by the time of Cromwell’s death in 1658, England had tired of his Puritan influences, and his son proved a weak successor. Charles II was brought back from his exile in France and monarchy was restored.

While somewhat kinder and more tolerant toward the Irish who had supported his return, including the Earl of Ormonde who had led the royalists in the Irish Confederacy, the plantation of Ireland continued. Known as the Merry Monarch, Charles II restored some of the gaiety that had been lost to England, and smoothed the way for new thought, invention and discovery in the latter part of the century as the Age of Enlightenment was dawning.

(Geoffrey Parker’s Global Crisis was a valuable source for this post)

The Prince of Glencurragh is set in 1634 prior to the great rebellion of 1641. It is a stand-alone prequel to my first novel, Sharavogue, which won first place for historical fiction in Florida’s Royal Palm Literary Awards. Both books are available on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Visit my website for more info, at nancyblanton.com.

The Prince of Glencurragh is set in 1634 prior to the great rebellion of 1641. It is a stand-alone prequel to my first novel, Sharavogue, which won first place for historical fiction in Florida’s Royal Palm Literary Awards. Both books are available on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. Visit my website for more info, at nancyblanton.com.

Today's post is reblogged from a guest post on Mary Anne Yarde's blog, "Myths, Legends, Books and Coffee Pots," (maryanneyarde.blogspot.com). In honor of the official publication of my new novel, The Prince of Glencurragh, this story is about one of my inspirations. While researching 17th century Ireland for my historical novel, The Prince of Glencurragh, I was stopped in my tracks by an arresting portrait of James Butler, the 12th Earl of Ormonde and the 1st Duke of Ormonde.

Ascending to earldom in 1634 at just 24 years of age, this earl became the Royalist leader of the Irish confederate forces in 1649, uniting the old English nobility, Catholics, and Irish rebel soldiers in a passionate stand against English dominance that was doomed to failure under the boot of Oliver Cromwell and his army.

The portrait captures an older Ormonde, looking magnificent in ceremonial robes as he is created the first Duke of Ormonde. He wears white satin trimmed in red and blue. Delicate hands grasp lance and sword; his jaw is proud, his eyes soulful and knowing. The long golden locks affirm his noble stature and remind me of a young, proud-faced Roger Daltrey, out to change the world in his own particular way – perhaps with similar sexual energy but without Daltrey’s penchant for fisticuffs.

No less appealing would have been James’s enormous wealth and power. He was born into a family tracing back to the Norman Invasion in the 12th century. His ancestor, Theobold Walter, was named Chief Butler of Ireland, and thus the name stuck as a surname and reminder to everyone of the family’s prominence and favor under King Henry II. The family seat became the great Kilkenny Castle from which they controlled the vast kingdom of Ormonde (basically including counties Waterford, Tipperary and Limerick).

Ormonde landholdings in southwest Ireland were second only to the Desmond earldom by the 14th century. Rivalry and skirmishes between the two earldoms escalated into a private war in the 1560s, one that infuriated Queen Elizabeth I, and in part led to the first Desmond Rebellion in 1569.

When James’s father Thomas died in a shipwreck in 1619, James became the nine-year-old heir to his grandfather Walter Butler, the 11th Earl of Ormonde, and was given the courtesy title of Viscount Thurles. Walter was a devout Catholic, much to the dismay of King James I who schemed for Protestant control of Ormonde estates, imprisoned Walter for eight years, and sent James to be schooled as a Protestant by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

When the earl was released in 1625, most of his estates were restored to him. James went to live with him at his house in Drury Lane, London.

While in London, James learned the Irish language, which was to serve him well later in life; and also met his cousin Elizabeth Butler, daughter of Sir Richard Preston, Earl of Desmond. Their marriage in 1629 ended the long-standing feud between the two families.

When his grandfather died five years later, James became the earl. In 1642, he was named the Marquess of Ormonde; and, after living with the king in exile during the Commonwealth years, in 1661 Charles II created him the first Duke of Ormonde.

But wait, there is even more to Ormonde’s appeal. Most of my research has focused on James’s early life, and my favorite story thus far is about his first attendance of the Irish Parliament in 1635. The new Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Wentworth, called the Parliament under King Charles I’s authorization, and was proud to have Ormonde on the roster.

In his biography of Wentworth, C.V. Wedgwood describes James Butler as a “high-hearted” nobleman: “Handsome, intelligent and valiant, he was also to the very core of his being a man of honor: loyal, chivalrous and just.”

And let’s not leave out dauntless (aka cheeky). When Wentworth ordered that the wearing of swords in Parliament would not be permitted, Ormonde told the official who tried to take his that the only way he’d get the sword was if it was “in his guts.” Wentworth summoned Ormonde before his council to answer for this behavior, and Ormonde arrived with his earl’s patent from the king. He threw it on the table. The king had made him earl, he said, and for anyone less than the king he would not ungird his sword.

“Wentworth [who was not yet an earl] conceded the force of the argument,” Wedgwood wrote.

Appealing as he was, Ormonde was not always everyone’s hero in life. As the Protestant in the family, he avoided the land confiscations that Catholic family members still suffered, and he was not above evicting Irish tenants if he believed he could earn higher rents from English ones. Still, when Ormonde died in 1688, he was lauded by poets of his time and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

In my novel, Ormonde is featured as a contemporary of the main characters who brings his significant power and influence, his chivalrous mindset, and his own agenda to the story, along with a fierce belief in fairness, justice, and love.

The Prince of Glencurragh, published in July 2016, is the story of an Irish warrior who abducts a young heiress to help restore his stolen heritage and build the Castle Glencurragh. He is caught in the crossfire between the most powerful nobles in Ireland, each with his own agenda. It is the stand-alone prequel to my first historical novel, Sharavogue, which begins with the arrival of Cromwell in Ireland, and follows the protagonist to her indenture on an Irish sugar plantation on the island of Montserrat, West Indies.

The Prince of Glencurragh, published in July 2016, is the story of an Irish warrior who abducts a young heiress to help restore his stolen heritage and build the Castle Glencurragh. He is caught in the crossfire between the most powerful nobles in Ireland, each with his own agenda. It is the stand-alone prequel to my first historical novel, Sharavogue, which begins with the arrival of Cromwell in Ireland, and follows the protagonist to her indenture on an Irish sugar plantation on the island of Montserrat, West Indies.

My books are available on amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. You can find more information and links on my website, nancyblanton.com

Have you ever heard a story of construction workers who died on the job being buried as part of the structure they were building? One of the first stories I heard was of men entombed within the Brooklyn Bridge. Apparently this is a myth, because a decaying body embedded in a concrete structure would then make that structure unstable. However, author David McCullough estimates 27 people were killed in various accidents or safety issues during the bridge construction.

I became curious about these myths after I happened across one story recently while researching the upcoming prequel to my historical novel Sharavogue. Call it serendipity, it was one of those magical, unexpected discoveries that make researching history fun, while providing genuine detail to spice up a novel. Centuries ago during construction of the enclosing walls for the town of Bandon, County Cork, Ireland, a young man was killed when a fellow mason working on a scaffold above him accidentally dropped his pickaxe. In the 1800s, the site was being excavated to build a summerhouse. When the workers found a large flagstone that gave a hollow sound when struck, they thought (hoped) they might have discovered an ancient stash of gold coins. Instead they found the skeleton of the poor mason, the pickaxe still under his skull, and his hammer and trowel by his side. In his pocket was a silver coin from the reign of Edward VI.

Little remains of this wall today, but stories live on, right?

Such as the Hoover Dam, where somewhere between 96 and 112 workers were killed between 1931-36. The myth has it that it was too costly to halt construction when a man was killed and so the concrete pour continued. But if this was true, the structure would not have been able to withstand the pressure of all that water over the years.

With the body of water that would become Lake Mead already beginning to swell behind the dam, the final block of concrete was poured and topped off at 726 feet above the canyon floor in 1935. On September 30, a crowd of 20,000 people watched President Franklin Roosevelt commemorate the magnificent structure’s completion. Approximately 5 million barrels of cement and 45 million pounds of reinforcement steel had gone into what was then the tallest dam in the world, its 6.6 million tons of concrete enough to pave a road from San Francisco to New York City. Altogether, some 21,000 workers contributed to its construction.

One story where site burials are not a myth is that of the Fort Peck dam site in Montana. Eight workers were caught in a slide there in 1938, but only two bodies were recovered.

My curiosity produced many stories of human sacrifice during constructions projects, as well as immurement. One from Germany concerned a mother who sold her son to be interred in the foundations of a castle, and then--feeling rather guilty--she threw herself off a cliff.

And a fascinating yet horrifying story is that of the Mole in Algiers, a massive breakwater started in the 16th century by the pirate-king Barbarossa. This structure was intended to provide defense against the Spanish, but the work was constant and relentless, requiring more than 30,000 Christian slaves for labor, and costing the lives of 4,000 slaves, or about five lives per foot of structure.

These days, thanks to safety requirements, construction deaths are fewer, workers are paid, and as far as I know are well cared for in case of accidents or deaths. In the US, private industry construction deaths per year are in the hundreds, not thousands. The leading causes of construction deaths are falls, being struck by an object, electrocution, or being caught between things.

I'll be visiting Bandon later this year for a little on-the-ground research, and will say a prayer for that poor mason who died there. Until then, keep it safe out there, and follow this blog for stories about my travels in Ireland starting in June, and for notices of when the new book will be out.

And in the meantime, embark on an adventure in Irish history! Sharavogue is the award-winning story of a peasant girl who vows to destroy Oliver Cromwell during his march of destruction across Ireland in the 17th century, and her struggle for survival on a West Indies sugar plantation.

And in the meantime, embark on an adventure in Irish history! Sharavogue is the award-winning story of a peasant girl who vows to destroy Oliver Cromwell during his march of destruction across Ireland in the 17th century, and her struggle for survival on a West Indies sugar plantation.

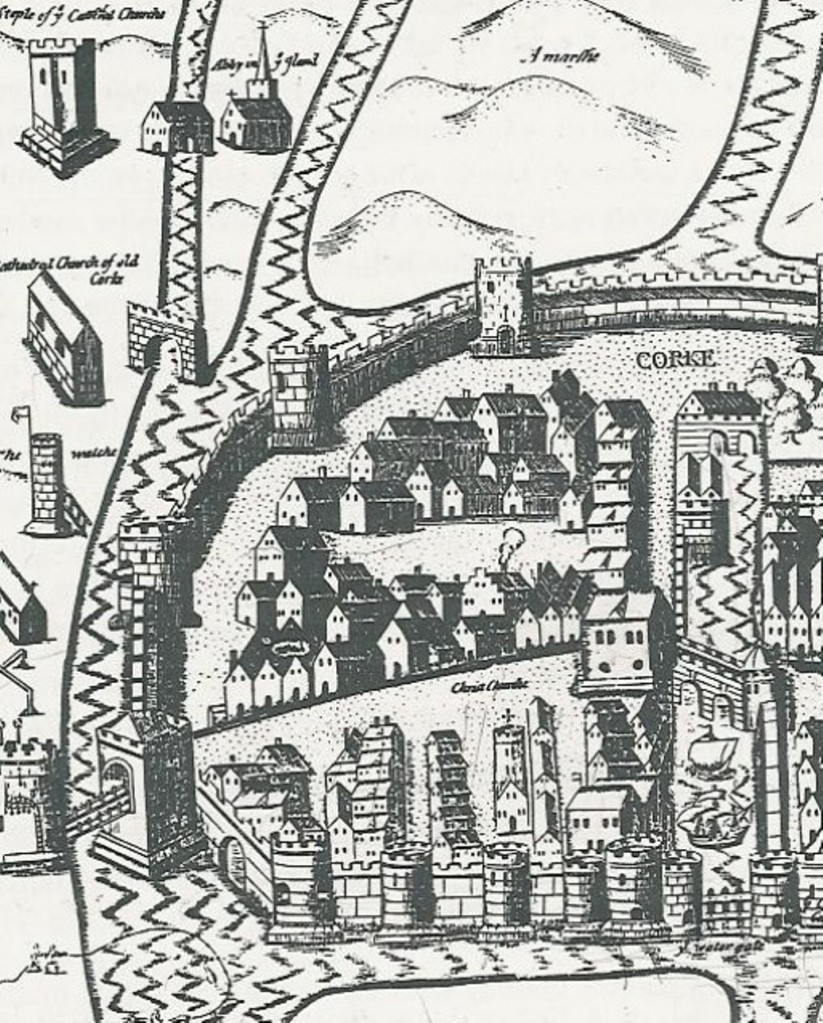

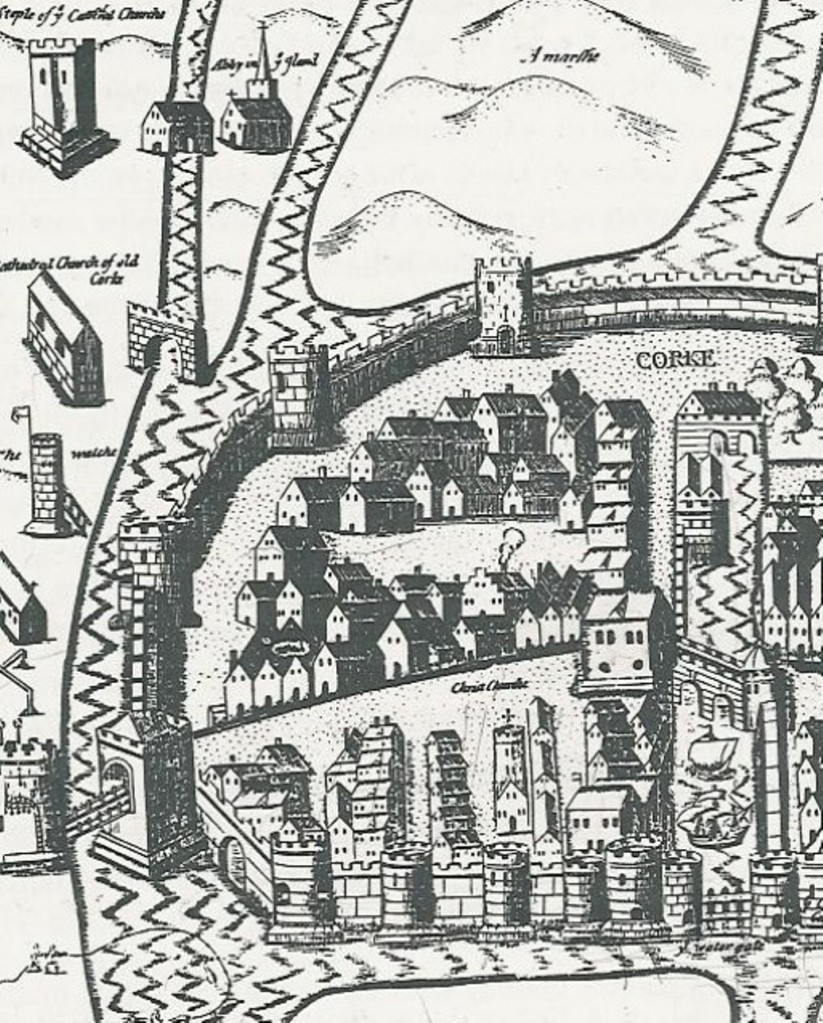

Roads have always been important to civilizations, from narrow dirt pathways leading to water and food supply, to major super highways that support international trade and industry. In researching the past, knowing the roadways is key to understanding the way communities lived and operated. That's why I was thrilled recently to discover the Down Survey Project online.

This is an amazing effort called the The Down Survey of Ireland Project, funded by the Irish Research Council under its Research Fellowship Scheme. The 17-month project was completed in March 2013. In short, the project combines digitized versions of surviving maps of Ireland from the 17th century (barony, parish and county level) with historical GIS (including various census and deposition sources) and georeferencing them with 19th-century Ordnance Survey maps, Google Maps and satellite imagery. Got that? Simple, right?

Roads have always been important to civilizations, from narrow dirt pathways leading to water and food supply, to major super highways that support international trade and industry. In researching the past, knowing the roadways is key to understanding the way communities lived and operated. That's why I was thrilled recently to discover the Down Survey Project online.

This is an amazing effort called the The Down Survey of Ireland Project, funded by the Irish Research Council under its Research Fellowship Scheme. The 17-month project was completed in March 2013. In short, the project combines digitized versions of surviving maps of Ireland from the 17th century (barony, parish and county level) with historical GIS (including various census and deposition sources) and georeferencing them with 19th-century Ordnance Survey maps, Google Maps and satellite imagery. Got that? Simple, right?

Well, no matter. If you have any interest at all in the history of Ireland, you will be amazed as I was to see the incredible public resource that this project has established.

Just as an example, for my book which begins in 1649, I can look up what landholders were in the area of my research, see exactly where their properties were located and what roads were in existence at the time. The old roads are represented as straight lines in the version I was able to bring up, and I doubt there were too many straight lines back then, but it does give me a general idea of locations and directions for ingress and egress. I'd say, for historical fiction it is a far better information source than my imagination.

Many thanks to the project team Micheál Ó Siochrú, David Brown and Eoin Bailey for creating this remarkable website. And thanks to Micheál Ó Siochrú also for his book God's Executioner: Oliver Cromwell and the Conquest of Ireland -- another valuable resource to me.

For England's roadways, historical novelist and blogger Patricia Bracewell has produced a four-part series on early English roads, featuring Watling Street, Ermine Street, the Fosse Way, and the Icknield Way. The series includes old maps and photos of present-day trails, and is featured on the English Historical Fiction Authors blog site.

Do you know of similar resources that might be helpful to authors? I'd love to know about them. Please comment.

Meantime: There are just three days left for my great giveaway of copies of Sharavogue on Goodreads. Sign up here!

Meantime: There are just three days left for my great giveaway of copies of Sharavogue on Goodreads. Sign up here!

Can the eyes in a portrait reveal the secrets in a person's character, or foretell their fate? Can a portraitist see through a person's eyes to the fears hidden behind them? In researching Thomas Wentworth, the first Earl of Strafford, for my book The Prince of Glencurragh, I am struck by my subject's eyes as captured by the eminent artist and portraitist of the period (1640s) Anthony van Dyck. The eyes are both striking and haunting with emotion as if the artist clearly saw through to Wentworth's inner feelings. And this was the artist's magic.

Born in Antwerp, van Dyck studied and painted throughout Europe before he moved to London in 1632, at age 33, to work for King Charles I.

"Van Dyck was now an artist with an international reputation and was widely traveled…He knew the art of pleasing distinguished and demanding patrons; he was equipped with a brilliant technique, and had at his command the whole repertoire of baroque painting. Above all, he possessed extraordinary imaginative powers, and, as a portraitist, an almost unequalled feeling for character and nobility of spirit," wrote Malcolm Rogers, in Anthony van Dyck 1599-1641, a catalog of work published for the artist's 400th birthday.

More than nobility, when I look into the eyes of Wentworth, I see anger, distrust, and a heightened fear. Wentworth began life in April 1593, the second son of a wealthy Yorkshire landowner, and ended as the closest advisor to the king. He is best known for his brief tenure as Lord Deputy of Ireland. He could not have known at the time the portrait was painted that he would be found guilty of treason by Parliament, for supporting the king's prerogative over the people's elected representatives, or that the king himself would sign Wentworth's death warrant. Wentworth was beheaded in 1641, and those eyes suggest he could see it all coming.

From that portrait, Macaulay's History of England described Wentworth this way: "That fixed look, so full of severity, of mournful anxiety, of deep thought, of dauntless resolution, which seems at once to forbode and to defy a terribly fate, as it lowers on us from the living canvass of van Dyke."

As Judy Egerton writes in the same book, "No portraits painted by van Dyck in England more brilliantly demonstrate his penetrating powers of perception than those of Charles I and Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, two sharply contrasting personalities."

Van Dyck completed many portraits of King Charles I, but no matter the pose, the king's eyes suggest sad resignation. Here is the king who fought Parliament to preserve the king's prerogative--basically his right to rule his kingdom through royal blood and divine right, without approval of Parliament--even though it led to a bloody civil war. But his eyes do not show the light of an impassioned leader, and sag as if he would rather close those lids than see what was coming. He and his Royalist army lost the civil war, and Charles was beheaded in 1649 by order of Parliament under the leadership of John Pym. Then the Parliamentary army, led by Oliver Cromwell, proceeded to Ireland to crush a bloody rebellion.

In addition to many portraits, van Dyck's paintings of courtly life and other settings do much to chronicle 17th century England. Van Dyck died in London in 1641 after a long illness. He was 42.

Part 9 in the "How I found my snow path to Dingle" series

Picking up where I left off on my series about my writing process for Sharavogue, today I am focusing on "What makes your book different from other books like it?" This is a question that might come during a media interview or from an anyone who is considering reading your book. To answer, I had to do my homework. When I selected the time period for my story, I searched for books in the Cromwellian years, the Interregnum, and on the bookends of that period during the reigns of Charles I and Charles II, the Restoration.

Specifically during Cromwell's time there were very few historical novels – I found only two, in fact -- that take place in this turbulent period. I have since found several more but I think I am safe to say I have written of a time often overlooked by other authors. So, for readers like me who also like to learn about history as they read, it might be a good choice. Sharavogue (the title of my novel but also the name of the plantation where the protagonist was indentured) also illuminates what life was like for slaves and indentured servants on the sugar plantations of the 17th century. These plantations were a boon to England’s economy but could not have been profitable without slave labor.

Specifically during Cromwell's time there were very few historical novels – I found only two, in fact -- that take place in this turbulent period. I have since found several more but I think I am safe to say I have written of a time often overlooked by other authors. So, for readers like me who also like to learn about history as they read, it might be a good choice. Sharavogue (the title of my novel but also the name of the plantation where the protagonist was indentured) also illuminates what life was like for slaves and indentured servants on the sugar plantations of the 17th century. These plantations were a boon to England’s economy but could not have been profitable without slave labor.

An intriguing and distinguishing fact is that a colony of Irish planters developed on the island of Montserrat, and they too had to own slaves. The focus is on an Irish colony and perspective rather than an English one.

My style of writing is also quite different. I have used devices and structure to keep the book light, exciting and fast paced, but still packed with story, action and historical information -- just enough, and interwoven as best I could so the story did not become a history lesson. My page count is under 300, not the tome of some historical novels. This required quite a bit of brutal editing, but I knew the costs of printing would make a larger book a difficult sell for an unknown author. Some people like this style -- the book keeps them engaged so that they read it all the way through in a day or two. (One reader laughingly complained that it was my fault she did not get her Easter cooking done). But others have told me they would have liked more time for contemplation by the characters.

My hope was always that after finishing the book my readers would come away satisfied, entertained and informed. I also hoped to tell a good story about the Irish, who have held my imagination since childhood. A recent reviewer captured the gist of the story just as I had hoped:

"The Irish were no different, after all, than the English. Cruelty reigned. We were without justice, without recourse. We were without hope." Fifteen-year-old Elvy Burke only wants to live up to her destiny. As the daughter of a great warrior, she dreams of being a leader of her people and a defender of her country. But Oliver Cromwell and his brutal army change her destiny. After cursing Cromwell to his face, she flees her village determined to find a way to kill Cromwell and free her land. She thinks that only Cromwell is brutal, but she discovers the hard way as she becomes an indentured servant in the West Indies, that the English do not have a monopoly on brutality. Elvy learns to survive and she finds kindness in unexpected places. She uncovers her own strengths as she fights her way back to her home in Ireland.

via Amazon.com: Customer Reviews: Sharavogue : A Novel.

This will be my last post in this series, unless any readers have additional questions that I will be most happy to answer. I look forward to any comments or suggestions for future posts. Best wishes and happy writing!

Part 8 of my "How I found my snow path to Dingle" series In this edition I'm focusing on another question asked about historical novels: "How is this relevant in today's society?" Sharavogue takes place in the 1650s, far removed in both time and location to what most of us experience today. But it is based in fact, so an obvious answer is to refer to the quote attributed to philosopher George Santayana, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it." Or the same with similar wording attributed to Winston Churchill and several others -- all the way to Jesse Ventura. Then there is the ever-positive Kurt Vonnegut, who says "I've got news for Mr. Santayana: we're doomed to repeat the past no matter what. That's what it is to be alive.”

As one who loves history and historical fiction, I sometimes wonder why writers need bother with trying to prove history relevant. It is, because it is. History is fascinating and woven from the lives and experiences of everyone who lived before us. Most humans love a good story, no matter what century it comes from. When I read historical fiction I also love learning about what life was like at a different time, and what circumstances caused things to be that way, and why people made the choices they did. It always in some way informs my own life without the author having to draw direct connections.

I recently read House Girl by Tara Conklin, which flips back and forth between pre-Civil War slavery and a present-day lawyer trying to attribute works of art to the slave girl. The whole story is about connecting past to present, and parts of it were quite good, but I found the historical portions by far the most interesting and well written, and the present-day portions sometimes feeling forced and distracting.

I recently read House Girl by Tara Conklin, which flips back and forth between pre-Civil War slavery and a present-day lawyer trying to attribute works of art to the slave girl. The whole story is about connecting past to present, and parts of it were quite good, but I found the historical portions by far the most interesting and well written, and the present-day portions sometimes feeling forced and distracting.

I also recently stumbled across The Traveler's Gift by Andy Andrews, a book someone had given my husband when he retired. It is basically a trip back in time to get seven philosophies for success, with the underlying message that each of us has a gift and the things we do have value and importance, whether we know it or not at the time. At one point we visit the Battle of Little Round Top where Col. Joshua Chamberlain's desperate last-minute charge is key to the Union victory there, which ultimately leads to the end of war, the end of slavery in America, and the growth of a superpower that is able to do good in the world. An oversimplification to be sure, but a strong message about relevance.

In my book, I chose to stay in the 1650s. While the relevancy is not mapped for readers as in the books I've just described, I think it derives from the characters themselves and the struggles and obstacles they work to overcome. One of my readers talked to me at length about the character Tempest Wingfield, who becomes a plantation master only because he inherited when his father died. She related strongly to his internal ragings against a life he never chose, and the sorrows he felt nonetheless for not being a better son, honoring and loving his father while he had the chance. Other readers related strongly to the pain of the poor choices Elvy Burke makes that lead her down more difficult pathways. As noted in an earlier post, Sharavogue itself (the plantation on Montserrat) is a character, passively supporting the plantation lifestyle in its own harsh existence.

Who has lost a loving parent and not felt deep regret? Who has not made poor choices in life and learned from them? And who has not witnessed injustices large or small and felt powerless to change them?

True relevance comes from the heart. But on a political level I must add that Oliver Cromwell (the bad guy in my book) remains today a relevant and controversial figure. I talked once with a British citizen who believed the commonwealth Cromwell established was the right and appropriate idea for his government, and the monarchy was irrelevant. Yet the Cromwell name is mostly associated with the 16th century Thomas who destroyed the Catholic monasteries, and the 17th century Oliver who slaughtered the Irish.

These stories and the jigsaw puzzle of factors that created them are impossible to deliver in a tweet or a Facebook post, and I worry about the lack of reading that could surely lead to the "forgetting" of history. (For example, I shudder when I hear women say they want to be stay-at-home moms, having lived through the time when women fought tooth-and-nail for the right to work and vote, and still struggle for equal pay.) But I take hope from something another writer once said to me: "People don't care about history until they realize they have one." And then it becomes all-important.

Part 6 in the series: How I found the snow path to Dingle I once dated both a Roger and an Osborne, and neither proved to be very good dating material, but they did not reach the villainous status of this guy: Roger Osborne. Straight out of history, I did not need to invent him as the bad guy in Sharavogue. He showed up on his own.

But more about him in a moment. This is a post about the characters in the story, and particularly the villains who actually drive the action. In Sharavogue there are three villains. The first one we meet is Oliver Cromwell himself. Cromwell and his New Model Army have just defeated the Royalists in a bloody civil war. Cromwell has emerged as England's new leader and has beheaded King Charles I in London. Now he comes to Ireland to cut down the Irish rebelling against English plantation on their soil.

Our heroine Elvy Burke confronts this powerful figure when he marches on her village. Cromwell had facial warts which helps add to his villainous image. It is Elvy's hatred and vow to kill Cromwell that drives her forward and commands her decision making.

Through a series of events Elvy soon confronts the second villain of sorts, Sharavogue itself. The word Sharavogue comes from the Irish meaning "bitter place," and it is the name given to a sugar plantation on the Island of Montserrat in the West Indies. The plantation system of the time depends on slave labor, and Elvy becomes an indentured servant struggling to survive against the customs, hard labor and the disease-ridden environment.

Because of her vow, Elvy cannot rest until she finds a way back to Cromwell to assassinate him. Thus, she seeks out the governor of Montserrat for assistance, and he is none other than Roger Osborne. In the 1650s, Osborne became governor of Montserrat when the original governor, Anthony Briskett, died. Briskett was revered for his vision and ability to engage and encourage fellow settlers and plantaton owners, and build a prosperous economy for the tiny island based primarily on tobacco crops. Briskett owned the best plantation on the island, married Osborne's sister Elizabeth, and they had one son. Roger owned the adjacent plantation, but thought the grass was greener on Briskett's side of the fence.

When Briskett died, Osborne's palms must have itched to get his hands on Briskett's plantation, but Elizabeth still wanted a husband and father for her young son. She married a Dutch planter and gentleman by the name of Samuel Waad.

What happens next is infamous for this period of history, and author Richard S. Dunn (Sugar and Slaves) lays it out like a play, listing all the characters by role. Picture Osborne, a massive spider, waiting for the perfect opportunity to weave his web and capture the fly.

Waad is a wealthy merchant and a bit of a dandy, but also very steeped in the rules of honor. When Osborne has Waad's house guest arrested for beating a local tailor with his cane (what was the tailor's offense, I wonder?), Waad is embarrassed and insulted. He writes a letter to Osborne that not only complains against the arrest, but goes on to call out Osborne's corruption and whoring.

Waad is now ensnared in Osborne's trap. Osborne is head of the militia, and calls the letter treason. Waad is arrested and, because it is a weekend, Osborne is able to call together only his cronies (and not the full militia) to determine Waad's fate. The action is swift. Waad is executed by firing squad. Osborne takes over his estate and management on behalf of his nephew, who is Waad's heir.

This story is true. I only wish I'd been able to find an image of Osborne to see if his countenance shows his personality. His interactions with Elvy are imagined and highly likely, but you'll have to read the book to find out more!

Part 4 in the series: How I found the snow path to Dingle I never would have guessed that one of the hardest things about writing a book is being able to describe it to someone in a succinct and compelling way. And when the story is set in a period that most people don't know? A nearly impossible nightmare. What was I thinking?

My publisher sent me some questions to help me prepare for a radio interview. Question 2: Summarize your book in one to three sentences. Here's what I came up with:

Sharavogue is a novel set in the turbulent 1650s, in the time of Oliver Cromwell and his brutal domination of Ireland. This is the tale of one girl’s vow of revenge, her journey through the lawless lands of the West Indies as an indentured servant, and her struggle to return to England to confront her sworn enemy and claim her destiny.

It's all true but I'm not sure compelling, and it doesn't quite get at the fun and adventurous aspects of the book. To do this, I really like the book Save the Cat by Blake Snyder. This book is aimed at screen writers but it is a fun, quick read, straight to the point and so helpful. You've got to be able to describe your book (screen play) in one sentence. "It's about a guy/girl who _______" fill in the blank. Simple, right? If only!

One thing I really liked about this book is that I realized I had basically and instinctively followed Blake's advice before I had even read it, in terms of the structure, the conflict, the beginning, middle and end. And I read the chapter on character development over and over again.

One thing I really liked about this book is that I realized I had basically and instinctively followed Blake's advice before I had even read it, in terms of the structure, the conflict, the beginning, middle and end. And I read the chapter on character development over and over again.

But mostly I liked the honesty and clarity about what works, what doesn't, and reminding us that writing is just one aspect of the book business. If you want people to read what you've written, you've got to sell it. Selling books and selling screenplays is a business, so you have to think in terms of what your customers want and care about.

The book's title refers to the idea that if you want readers to care about your main character, he or she can and should have flaws, but must also do something early on to win their hearts. Save the cat! In my case, my character tries to save her village. She fails, but hopefully by the time that happens the readers have already started to care about her and want to know what happens next, so they keep turning the pages.

Honestly, I still struggle with those one to three sentences. I've practiced saying them, described the book to many readers, and still there are times when I get a blank expression in return. Maybe one day I'll write about a time that people can immediately relate to, and I'll work in an irresistible cat.

Part 3 in the series: How I found the snow path to Dingle

As noted in my last post, my research was leading me to believe I had a book on my hands, or at least I hoped so. I had already finished my first novel but it was lengthy and meandering, and though dear to my heart because it was written as a tribute to my father, I knew it was not marketable as it was and could not see a clear way to fix it. I had already started attending writers' conferences to learn, and found them both helpful and destructive.

As noted in my last post, my research was leading me to believe I had a book on my hands, or at least I hoped so. I had already finished my first novel but it was lengthy and meandering, and though dear to my heart because it was written as a tribute to my father, I knew it was not marketable as it was and could not see a clear way to fix it. I had already started attending writers' conferences to learn, and found them both helpful and destructive.

In particular, I loved the Surrey International Writers Conference in British Columbia, where I met Diana Gabaldon (I've attended several times), and the Historical Novel Society where I met Margaret George, among others. I did not care for the Pacific Northwest Writers Conference in Seattle, where the speakers' attitudes seemed to be "we're published, you're not and never will be." When I sat down for lunch and realized everyone at my table had the same impression, I knew I'd never go back to that one. The Algonkian Writers Confererence at Half Moon Bay was limited to 15 people who had achieved a certain level of proficiency. I found it intimate, individualized, bonding, positive and instructive.

Among the things I learned was that as a new writer, you need to keep your word count down, because publishers are less likely to make an expensive investment in a new writer, and thick books are costly to print. The recommendation was between 120,000 and 150,000 words. It is tricky with historical fiction, because there is more to explain and describe, but it can be done. (As an example, Sharavogue comes in at just over 117,000 words and the printed book is 292 pages.)

I also learned, as we all know already, you must hook the reader with your first line, your first paragraph, your first page. There are certainly books I've read that did not hit this mark, but I think unless you have a friend in the publishing industry or something else up your sleeve, it's something to strive for. Think of an agent or editor sitting at a desk surrounded by stacks of manuscripts. He or she will be looking for a reason to eliminate some. Don't give them one. I rewrote my openings countless times. (How do you know when it is done? As another author said recently, you just have to write from the heart and hope for the best.)

At these conferences, editors and agents often speak on panels or you can learn what they are looking for during 10-minute one-on-one sessions booked in advance. I remember hearing one agent say enough already with the Tudor period. I saw that comment repeated on another agent's website. So in part that's the reason I decided to look for a time different than Henry VIII, Anne Boleyn or Elizabeth I. I decided to choose a time not often covered in books (the road less traveled, if you will); a time very important in Irish history that spoke to my own Irish heritage. And, one of my goals would be to help illuminate this new time period, because I believed readers of historical fiction wanted, just as I do, to learn about history as they read a good story. From Diana Gabaldon, while falling in love with Jamie I also learned about the battle at Culloden and the Scottish rebellion against English rule.

Of course, the danger in choosing a different time period is the agents and editors also don't know it, so they don't know how to sell it. I deeply admire Hilary Mantel who, with her brilliant books Wolf Hall and Bring Up The Bodies, found a way to approach the Tudor period from a completely different viewpoint: that of the infamous Thomas Cromwell.

I chose Oliver Cromwell, distantly related in the next century whose name still stirs hate among the Irish and admiration among some English, but definitely controversy among all. And I did choose this period, the Irish rebellion of 1641 through Cromwell's march of 1649, but it also chose me. Once I focused, books and articles came to me that I had not really searched for, and then because of those I was drawn to other resources that I sought relentlessly for months. Pieces began to come together like I big, messy jigsaw puzzle.

All good stories must have a beginning, a middle and an end. Fairly early on, I knew the beginning of my book, and then I knew how it would have to end. I really had no idea what would happen in the middle. It took years of research and discovery, but slowly the middle began to take shape and fill in. On that day when I realized the two ends would actually meet, the elation was magnificent!

Part 2 in the series: How I found the snow path to Dingle At the end of my last post, I began the adventure to discover the meaning of the phrase in my head, "the snow path to Dingle" which ultimately led to the book Sharavogue. Where else could my research begin, but Dingle? Many tourists to Ireland venture out on this far-west peninsula, but if you have never been there it is an amazing mix of sugar-white beaches, dark clumpy bogs, castle ruins, rocky mountain passes, harbor towns with fishing boats bobbing on the water, lush green pastures, lively pubs and gourmet restaurants tucked amid colorful village shops and businesses. Most would never guess the horrors that once took place there.

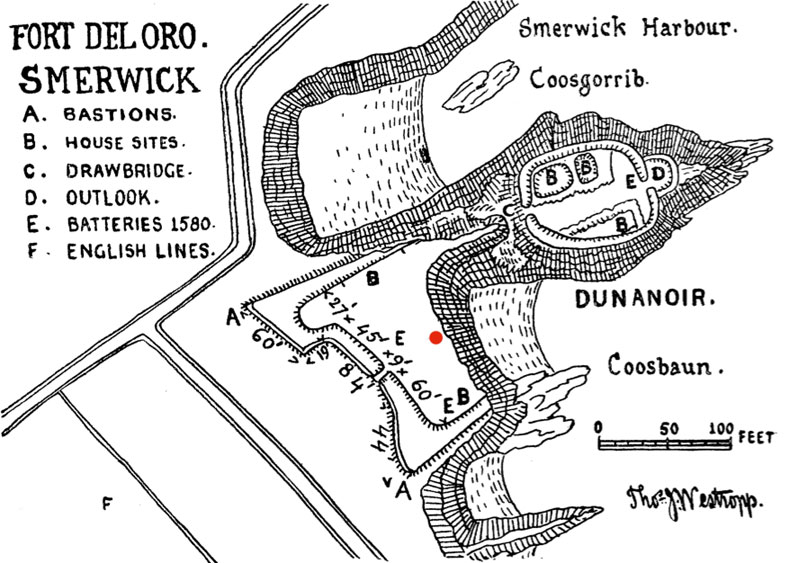

I started my research on the Internet, but this was several years ago and the web was not the robust information resource that it is today. Still, one of the first things I found was the story of the Seige of Smerwick. According to one source:

Smerwick was originally a Viking settlement and its name originates from the Norse words ‘smoer’ and ‘wick’ meaning ‘butter harbour’. Although denoted as Smerwick on charts the area is now officially known by the Irish name ‘Ard na Caithne’, meaning ‘height of the arbutus’ or strawberry tree.

It is a sweet name that helps to obscure a bitter past. In 1580, 600 Italian and Spanish troops landed here, funded by the Pope to aid a rebellion against English forces in Ireland. The garrison became isolated on a narrow tip of the peninsula, with English artillery on the land side and naval forces on the sea. Earl Gray laid seige to the garrison and their defenses crumbled after three days. Gray rejected their request for terms, insisted on unconditional surrender, then sent his bands in to execute the 600, sparing only those of higher rank. The soldiers were beheaded, their bodies flung into the sea and their heads buried in a field. The ranking offers were offered life if they renounced their Catholic faith, and if they did not their legs and arms were broken in three places, they were left to suffer for a day, and then hanged.

It is a sweet name that helps to obscure a bitter past. In 1580, 600 Italian and Spanish troops landed here, funded by the Pope to aid a rebellion against English forces in Ireland. The garrison became isolated on a narrow tip of the peninsula, with English artillery on the land side and naval forces on the sea. Earl Gray laid seige to the garrison and their defenses crumbled after three days. Gray rejected their request for terms, insisted on unconditional surrender, then sent his bands in to execute the 600, sparing only those of higher rank. The soldiers were beheaded, their bodies flung into the sea and their heads buried in a field. The ranking offers were offered life if they renounced their Catholic faith, and if they did not their legs and arms were broken in three places, they were left to suffer for a day, and then hanged.

This story was horrible and unforgettable to me, though I was not sure I wanted to write about it. In the end I gave it only a passing mention because I chose to write of a not less brutal time about 80 years later. What this story did was ignite my passion for research into the dramatic history of Ireland. And I learned how magic and exciting research can be.

One of the best things I did was become a "friend" of the University of Washington Library, which means I paid a small fee for access to books and documents. I learned that the library doesn't "stock" everything, but populates its shelves with things as professors and research assistants request documents and publications for their research projects. Then they are available to the lay person. I learned not to be disappointed if the book that I wanted was not sitting in the stacks where it was supposed to be, because I would inevitably find even more interesting things waiting for me that I had not found in the catalog. Just to pick up those books and thumb through them brought magical surprises that led me in specific directions.

One day I stumbled across a book that had interviews with Irish people describing the devastation left in the wake of Oliver Cromwell's march in 1649 and 1650, and one man's description of the horrible omen the he was certain foretold Cromwell's coming: It was a full yellow moon encircled by blood and cleaved in two.

I was fascinated. I had found a time that I needed to know much more about. I was hooked.

I feel it is a great honor when readers share with me that they read my book, Sharavogue, and then describe the parts that affected them most. In a few cases it has actually sent a chill up my spine because, well, it is every writer's dream that her writing will be enjoyed and will actually touch someone. In that sense, it is really a dream come true.

People ask all sorts of questions, but several have told me they'd be interested in learning about my writing process. I'm flattered, and a little embarrassed. I've been less than methodical in my research, so probably not a good model. But, everyone has their story, right? So in honor of my new friend Joan Butler, today I'm starting a series of posts about just that. I'm expecting it to be about 10 or 12 posts, and will gladly take questions from readers to cover a specific topic.

I feel it is a great honor when readers share with me that they read my book, Sharavogue, and then describe the parts that affected them most. In a few cases it has actually sent a chill up my spine because, well, it is every writer's dream that her writing will be enjoyed and will actually touch someone. In that sense, it is really a dream come true.

People ask all sorts of questions, but several have told me they'd be interested in learning about my writing process. I'm flattered, and a little embarrassed. I've been less than methodical in my research, so probably not a good model. But, everyone has their story, right? So in honor of my new friend Joan Butler, today I'm starting a series of posts about just that. I'm expecting it to be about 10 or 12 posts, and will gladly take questions from readers to cover a specific topic.

This being first in the series, I'm starting at the beginning -- how I got started writing this book in the first place. So hold on to your jammies, here goes. We're going back. Way back:

I'd wanted to be a writer since I was a little kid. Alone in my bedroom, maybe 10 years old, I wrote little stories about dogs and squirrels and gave them to my mother to read (top secret, of course, because if my sisters had known about them they'd have teased me relentlessly). And Mother in Heaven forgive me, once I even had a story about a swan on a lake. (I know, it's been done...) My poor mother had to come listen to it accompanied by me on my ukelele (I thought the instrument was cute and had to have it, but never actually learned how to play it...). My father always called me "the dreamer." Little did he know.

In grade school and then college I continued my dreams. I dabbled in English, and then Education, until my roommate finally convinced me: If you want to write, study journalism! I did and have never regretted it, but in a way it distracted me from those stories. And my career drifted even further, from journalism to corporate communications, until I believed my stories were gone for good.

The last time I saw my father alive was in the fall of 1996. By then I was married and living in Seattle. I was visiting him in Florida. He took me to lunch and asked, "When are you going to start writing again?" I don't think he knew about the squirrel stories, but had always been proud of the newspaper ones. I shrugged and said I didn't know if I could write anymore. My writing was all bureaucratic now.

He said, quite simply, "You'll write when you're ready."

We lost him in March of the following year. It was almost exactly a year after his death that I was awakened from a deep sleep, as sure as if someone had shaken me, and a phrase was in my head: A snow path to Dingle. A snow path to Dingle -- a phrase so strong and nonsensical, it had to come from somewhere, for some reason, and it refused to leave. Hardly having any choice, I resolved to do some research to discover its meaning.

And, because I already loved historical fiction, and had twice visited Dingle in the west of Ireland to explore our family's Irish heritage, I felt I had a basic foundation and a clear place to start. And so I was off...on a real adventure.

Three hundred and sixty-four years ago this month, England's King Charles I was beheaded by direction of Parliament, with General Oliver Cromwell leading the formalities. King Charles was charged with treason, having just lost a bloody civil war and continuing to plot with is pesky royalist friends.

Charles I was considered a bad king. He signed away business monopolies to his favorites without regard to the consequences, taxed greedily and without consent of Parliament, and spent lavishly on his grand art collection. He thought he had the right: the God-given King's Prerogative, to which Parliament did not subscribe. Plus, his wife was Catholic when the country most definitely had gone Protestant and Puritan.

Three hundred and sixty-four years ago this month, England's King Charles I was beheaded by direction of Parliament, with General Oliver Cromwell leading the formalities. King Charles was charged with treason, having just lost a bloody civil war and continuing to plot with is pesky royalist friends.

Charles I was considered a bad king. He signed away business monopolies to his favorites without regard to the consequences, taxed greedily and without consent of Parliament, and spent lavishly on his grand art collection. He thought he had the right: the God-given King's Prerogative, to which Parliament did not subscribe. Plus, his wife was Catholic when the country most definitely had gone Protestant and Puritan.

In her book, Rebels and Traitors, Lindsey Davis does a nice job of describing the dramatic scene:

The King knelt before the block. He spoke a few words to himself, with his eyes uplifted. Stooping down, he laid his head upon the block, with the executioner again tidying his hair. Thinking the man was about to strike, Charles warned, 'Stay for the sign!'

'Yes, I will,' returned the executioner, still patient. 'And it please Your Majesty.'

There was a short pause. The King stretched out his hands. With one blow of the axe the executioner cut off the King's head.

The assistant held up the head by its hair, show the people, exclaiming the traditional words: 'Here is the head of a traitor!' The body was hurriedly removed and laid in a velvet-lined coffin indoors. As was normal at executions, the public were allowed to aproach the scaffold and, on paying a fee, to soak handkerchiefs in the dripping blood, either as trophies of their enemy, or in superstition that the King's blood would heal illness.

Kings had been killed before, of course, but most typically in battle by an opposing army, or they were murdered by some ursurper using a blade or a poison. But this was the first time a nation's government had executed a king. Would God allow that? Apparently so, and it sent a shockwave throughout Europe's monarchies.

It also freed Oliver Cromwell to begin the episode for which he is most hated and remembered -- especially by the Irish. A rebellion against the English plantation of Ireland had begun eight years earlier. With the civil war won and the king dead, Cromwell was now free to descend with Parliament's army upon Ireland to crush the rebels. And that he did. This is where the term "decimated" comes from: It refers to Cromwell's order for his soldiers to execute every 10th Irish rebel, and the rest were shipped to the West Indies to work as slaves or die. This is where my story begins, in Sharavogue.

I was just wondering today (a little behind everyone else, it appears) what a 17th century Christmas really was like. In the time of Charles I and Oliver Cromwell, the Puritans enjoyed a lot of power in Parliament, and it turns out they actually canceled Christmas by ordinance in 1652: no holiday, no mince pies, no decorations, no church services. If only they'd had Dr. Seuss to remind them that Christmas happens anyway, even if you take away the gifts and the trappings. Since Christmas Day really isn't the day of Christ's birth -- the day was conscripted for Christmas because it was already a pagan celebration day and it was easier to turn more pagans to Christianity if they still got to party on their favorite day -- the Puritans claimed the day had no basis in the Bible and therefore should be banned. A great description of this episode in history is covered by another blogger, TrickyGirl, who includes a recipe for mince pie: Another Kind of Mind.

The topic also was covered a few days ago by Rachel Schnepper for the New York Times: The Puritan War on Christmas.

The Puritan leader of the time and uncrowned King of England Oliver Cromwell gets blamed for a lot of things (he's the bad guy in my novel Sharavogue, for instance), but the Cromwell Association says we should not blame The Lord Protector for the ban on Christmas:

"There is no sign that Cromwell personally played a particularly large or prominent role in formulating or advancing the various pieces of legislation and other documents which restricted the celebration of Christmas, though from what we know of his faith and beliefs it is likely that he was sympathetic towards and supported such measures, and as Lord Protector from December 1653 until his death in September 1658 he supported the enforcement of the existing measures."

Still, there was much joy among the English people when Christmas was restored along with the monarchy and King Charles II.

The Puritan ban on Christmas was big for the New England colonies, but eventually the drive for religious freedom made Christmas a major holiday in our nation. Now, of course, we have so much religious freedom that Christmas again suffers a ban of sorts: If U.S. government agencies will display signs of the Christian holiday, they must also display the symbols of every other religion, including atheism. The irony is that in some cases these agencies just put an unadorned fir tree on display, and presto, we are right back to pagan symbolism!

Miles Sindercombe was a fascinating surprise to me as I researched my book, Sharavogue. I was looking for any assassination attempts on the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell in the mid-17th Century, because my protatonist would be attempting to do exactly that. Being American, I had never heard of Sindercombe, so I wonder if he is better known in the UK. He tried twice and failed to kill this uncrowned king. Wikipedia gives a pretty good history of assassination that's worth the read, tracing it back to 1080 and the Order of Assassins founded around the time of the Crusades. In Cromwell's case the attempt must have come as no surprise, at least to his security crew, considering Cromwell had won a bloody civil war and then beheaded the king, Charles I. He also had led a brutal march across Ireland to put down a rebellion. The man did not lack for enemies and controversy over him continues to this day.

What's interesting is that Sindercombe seems to be an unlikely and tragic figure. I was unable to turn up an illustration of him, but it seems he was a thin, mild-mannered sort who went by the name of "Fish." A former soldier, apprentice to a surgeon, he aligned with others he met in taverns (i.e. Edward Sexby) who had fought against the Royalists but had fallen out with Cromwell's policies.

The first plan against Cromwell was to shoot up his carriage as it slowed to go through a narrow pass on the way to Hampton Court. But, Cromwell decided to go by boat so the plot failed. The second attempt was to shoot Cromwell from the window above the side exit from Westminster Abbey where Cromwell would pass after hearing a sermon. But Crowell was surrounded by crowds, they could not get a good shot, and the plot was discovered. Sindercombe and his accomplices were arrested. Sexby was questioned by Cromwell himself, was sent to prison and soon died of a fever. He was the lucky one. Sindercombe was sentenced to a traitor's death (the whole hideous bit, with the hanging, disembowelling while still alive, and body parts on pikes for display). To help him avoid this, friends sent him letters coated with arsenic which he rubbed on his face and neck, poisoning himself to death the night before his planned execution. His body was buried beneath the highway where no one could mourn him.

Cromwell made light of the whole thing, calling such attemps on his life "little fiddling things," so as not to encourage the Royalist-spread rumor that he so feared assassination he was drinking himself to death. My recent visit to the Cromwell Museum in Huntingdon confirms the rumor of his fear, if not the drinking. A display shows an inlaid cabinet of perfumes, ointments and soaps--a gift from the Grand Duke of Tuscany--that he never used, most likely fearing a poison. Cromwell's doctor is quoted as saying "He is possibly afraid that they will be bitter, being fearful of his own shadow, so to speak, and living in constant apprehension of everything for he trusts no one."

Cromwell made light of the whole thing, calling such attemps on his life "little fiddling things," so as not to encourage the Royalist-spread rumor that he so feared assassination he was drinking himself to death. My recent visit to the Cromwell Museum in Huntingdon confirms the rumor of his fear, if not the drinking. A display shows an inlaid cabinet of perfumes, ointments and soaps--a gift from the Grand Duke of Tuscany--that he never used, most likely fearing a poison. Cromwell's doctor is quoted as saying "He is possibly afraid that they will be bitter, being fearful of his own shadow, so to speak, and living in constant apprehension of everything for he trusts no one."

History has Cromwell dying of natural causes in 1658, but after his death his own doctor, secretly (or suddenly?) a Royalist, was rumored to have poisoned him in favor of the return to monarchy.

Following the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln was not so fortunate. His life is revisited in the new movie, Lincoln, just out this week. His assassin John Wilkes Booth was trapped in a burning barn and shot by a US cavalry officer, and died from the wound hours later. It is an unforgettable episode in our history, unfortunately repeated several times.

When I talk to people about the setting of my book Sharavogue, and mention the name Cromwell, I get confused looks: cognitive dissonance. Most people have heard of Cromwell, but I am writing about the 17th century, and the man they tend to think of by that name lived in the 16th century, serving the court of King Henry VIII. After Cardinal Woolsey fell from favor by failing to produce this king's annulment from Queen Catherine of Aragon, his protege Thomas Cromwell took up the work. It was Thomas who orchestrated the marriage to Anne Boleyn, and who dissolved and destroyed the country's monasteries and churches to fill the king's coffers with their riches. By 1540, Thomas himself fell from favor and was executed for treason, though good Henry later regretted it. More than a century later, Oliver Cromwell gained prominence through the Parliamentary army's victory in the English civil war. And for anyone with a drop of Irish blood in their veins, it is this Cromwell who makes that blood run cold. Oliver shook the foundations of Europe's monarchies when he beheaded King Charles I for treason in 1649, and later became Lord Protector (rather than king) of the English Commonwealth. But between those two historic events, he marched his army across Ireland to massacre the Irish people and crush a rebellion. If you've ever heard the term "decimation," it comes directly from his practice of killing every tenth man among his captives, and shipping the rest to the West Indies to work until they died.

Ironically, Oliver Cromwell wasn't really a Cromwell at all. He was a Williams. As Antonia Fraser deftly explains in her definitive biography, Cromwell, Oliver descended from Thomas Cromwell's sister Katherine, who married Morgan Williams. Their son Richard adopted the "more celebrated" Cromwell name and this continued to be used by Richard's descendents. Apparently it was not uncommon during this time for families to adopt the name of a famous relative in hopes of benefitting from that prominence.

But wait, the ironies continue. The true descendents of Thomas Cromwell became Earls of Ardglass, and this family supported the Royalist side, opposing Parliament when Oliver led that army to victory. And though Richard Williams took the name Cromwell as a means to elevate his family, eventually it backfired as the two Cromwells became one in the modern mindset, and in addition to the brutal killings in Ireland, Oliver Cromwell also takes the blame for the hated archtectural destruction perpetrated by Thomas.

Oliver does retain his fan base, however. Though hated for his violence and brutality in Ireland and his Puritan oppression of the English court, he is revered by some for his military prowess and for introducing the idea of a commonwealth for England.

Nancy Blanton is the award-winning author of Sharavogue, a historical novel set in 17th Century Ireland during the time of Oliver Cromwell, and in the West Indies, island of Montserrat, on Irish-owned sugar plantations. She has two more historical novels underway, as well as a non-fiction book about personal branding, Brand Yourself Royally in 8 Simple Steps. She also wrote and illustrated a children's book, The Curious Adventure of Roodle Jones, and co-authored Heaven on the Half Shell, the Story of the Pacific Northwest's Love Affair with the Oyster.

“Like reading The Three Musketeers for the first time!” —reader review of The Prince of Glencurragh