What IS this thing about history?

/Recently when I opened my Facebook account, an unexpected memory awaited. It was this picture, taken in 2001 to promote a new book that was a long time in coming, and a source of pride for these three co-authors, Terry Nosho, David G. Gordon, and yeah, that’s me in the middle.

Time has altered our faces, but not the joy and passion for that book...that book...

One day, about a year and a half before this picture was taken, a young man in jeans, mud boots and a rumpled shirt came into my office. He plopped down on our worktable a most magnificent thing: a scrapbook of enormous proportions, with a kelly-green cover nearly the size of my refrigerator door, and spiral-bound pages stacking three inches high.

“My grandfather’s an oyster grower. He’s been keeping this thing for years, sticking this and that in it,” the man said. “Newspaper articles, pictures, restaurant menus, napkins, all sorts of things. He wants to know if you can do something with it. Anyway, it’s yours now.”

Well, not mine, exactly, but the grant program for which I worked, housed with the School of Fisheries and Oceanography at the University of Washington. Our offices were repurposed student housing, a stone’s throw from Montlake cut between Lake Washington and Lake Union where the University’s famed rowing team practiced.

Our program’s educational and research support for the oyster industry, led by Terry Nosho, was well regarded as perhaps the only positive attention paid by anyone to the health and survival of oyster farming.

The whump of the scrapbook on the table was enough to draw my team from their desks: David first, being most curious; then Robyn, the graphic designer; then Susan, the webmaster. We turned the first page. I can’t speak for the rest of them but I was immediately spellbound. Those pages contained a world: not just the history of Washington state’s oyster resource, but of the farming and consumption of oysters, of their culture, and the culture of the families that made a living from them, can labels, matchbook covers, cartoons, and so much more. What could we do with such treasure?

And to me it truly was treasure, as I considered the thoughts and hands and eyes of the person who had compiled this book faithfully and consistently over the decades, the stories this book told and the stories that were never told.

On David’s thoughtful lead—he was already a published author several times over— we perused that scrapbook for different threads that we could weave into a historical look at the world of Washington oysters, complete with recipes and gorgeous photography of Washington’s iconic coast. The result was Heaven on the Half Shell, the Story of the Pacific Northwest’s Love Affair with the Oyster.

It was a powerful experience. It became an opportunity to capture its essence in an idea, grow the idea into a viable project, and then produce a book that not only encapsulates time, but also stands the test of it.

A new door had opened. The love of history and adventure ran in my veins—my favorite book as a child was Robinson Crusoe—and now I learned how to research things, what to look for, how to turn history and discovery into story, and turn story into a touchable, colorful, ink-scented book for anyone to enjoy.

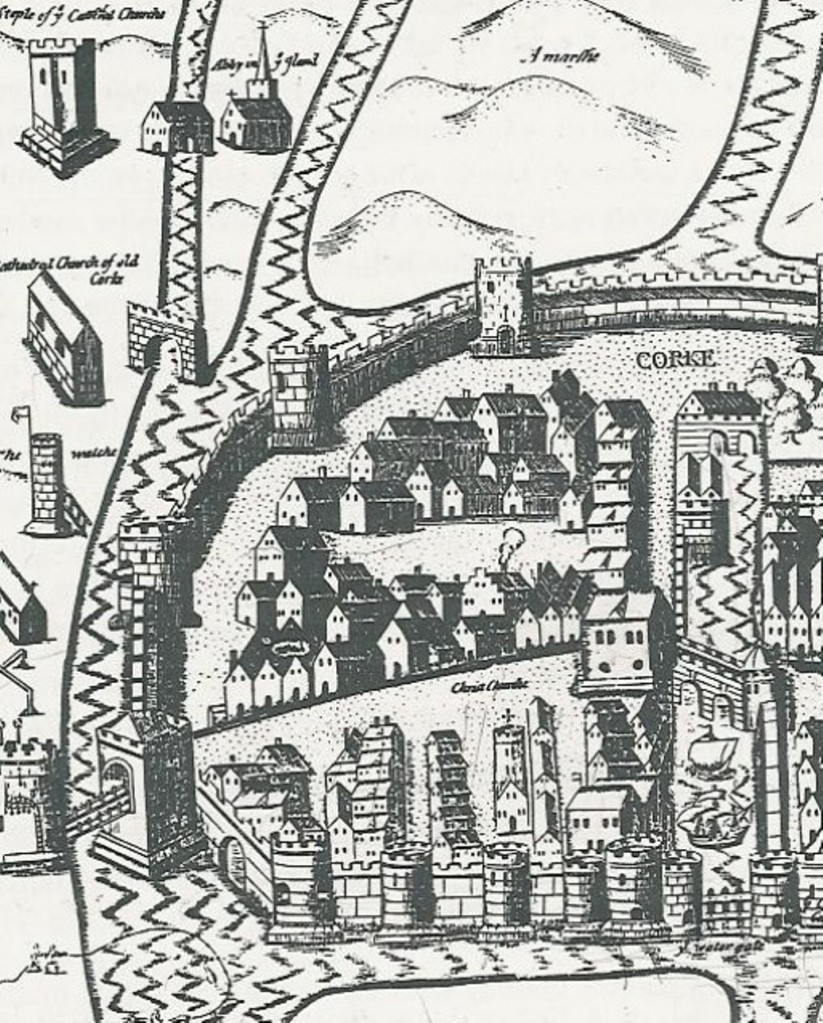

It wouldn’t be long before my own history came knocking; before passion, experience and heritage merged, and I had to find out. I had to know. What happened in the lives of my ancestors? Did they actually live in...castles? Did they suffer? Did they fight? Did they rise? The truth eludes me. The facts are veiled or nonexistent. There is conjecture. Mystery. Hearsay and propaganda.

I search through the documents, books and biographies available, and fill in the blanks as I best I can. It’s a little like prying open an oyster shell, but not as sharp. And four books later I begin again, wondering still why I love it so, this thing with history?

Last month at the Amelia Island Book Festival in Florida, I received another gift: the opportunity to chat with New York Times best-selling author Margo Lee Shetterly. If you do not recognize the name, you’ll recognize her book: Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race.

Not historical fiction, but classified as narrative non-fiction, her book required a great deal of research, and when I told her that the former journalist in me greatly admired the work she had done to create that book, we connected on the love of research.

She lamented that several of the people she’d hoped to interview for her next book had already passed away. The same was true when we were researching the oyster book. People had either passed away or were too distrusting of “government” to speak with us. I replied that, writing about the 17th century meant all my people had passed away, but fortunately in those days they wrote letters. What will happen, we wondered, when such detailed written documentation of emotion and experience is lost?

I believe we will find it still, in blog posts and videos, in personal journals, in the work of historians, archaeologists and anthropologists who will always dig for the truth.

If history infiltrates other thoughts, usurps other interests, occupies every bookshelf, makes you the geek at parties, and so on—then it is both gift and responsibility. The study of history becomes a joyful treasure hunt that not everyone seeks or understands, but the responsibility is to give attention and meaning to a particular time and people who lived it.

With the help of inspiration, you get to share these discoveries in a way that engages people so that they get those same messages. Carry on!

Happy after my first novel won gold at the Florida Writers Association.

Embark on an adventure in Irish history -- 17th century, that is, with

Embark on an adventure in Irish history -- 17th century, that is, with