Tracking the Prince: Kanturk Castle

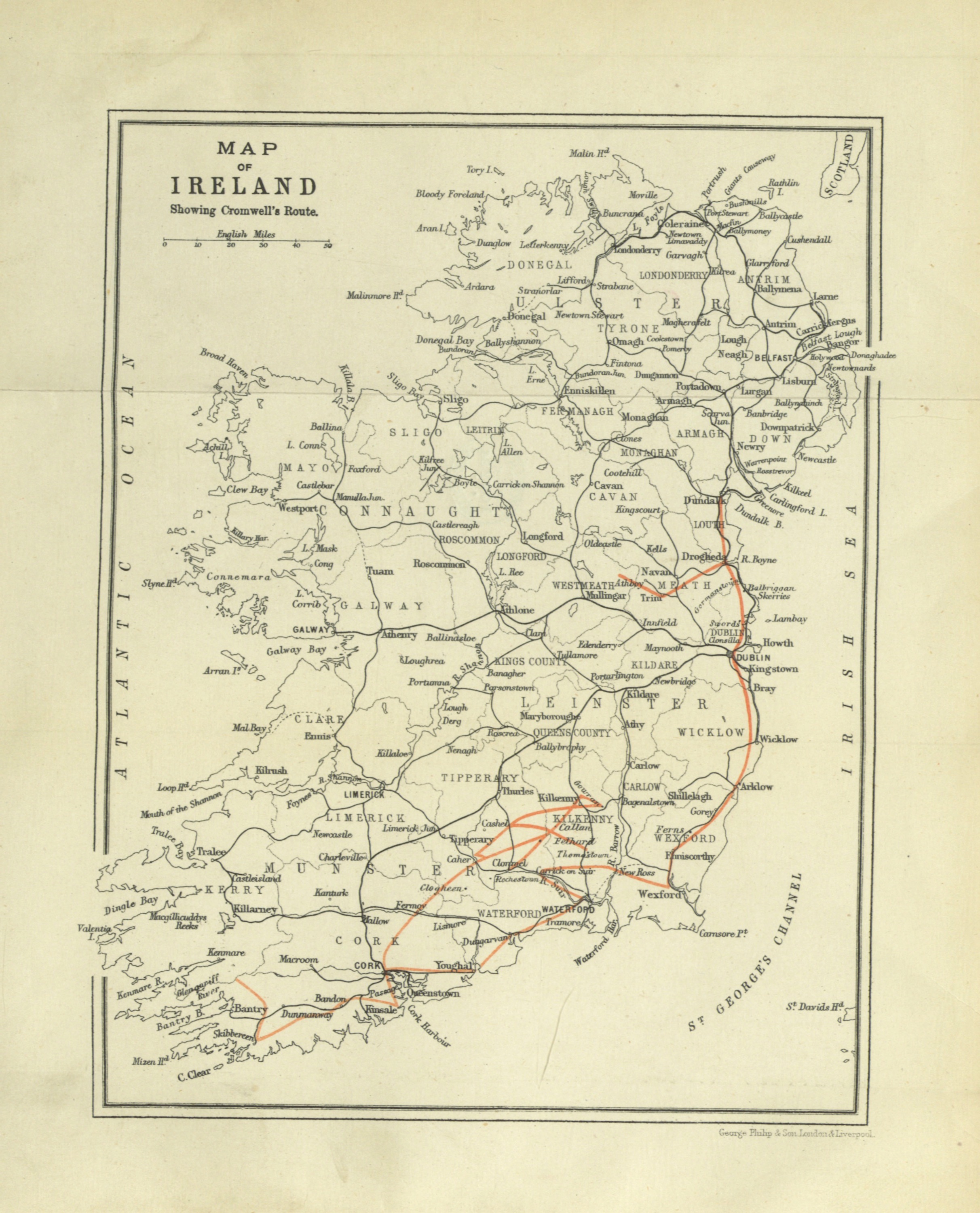

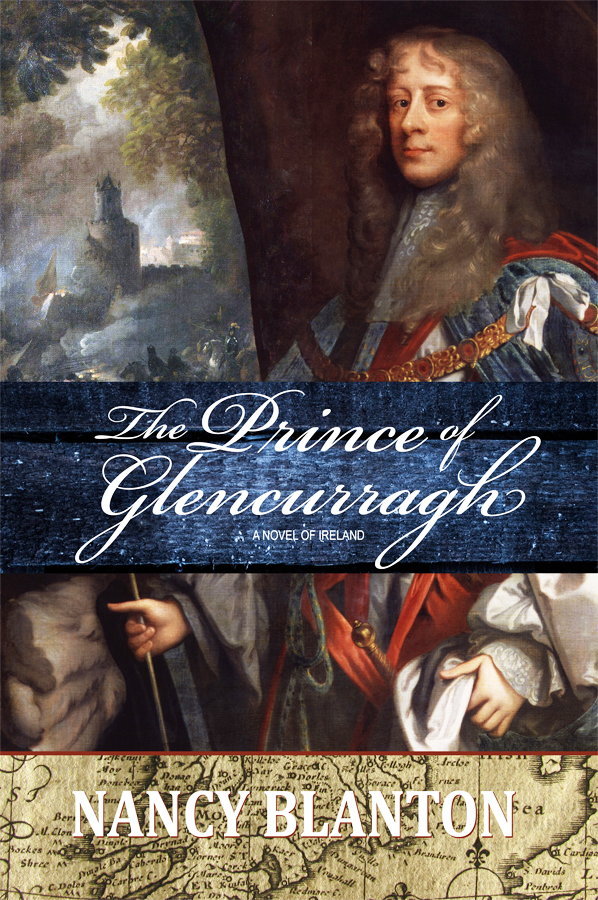

/Today I begin a series featuring sites I visited in Ireland while researching my second novel, The Prince of Glencurragh. This book takes place in mid-17th century Ireland, when castle towers are losing their significance and the order of the day for the rich and powerful is a grand, fortified manor house that demonstrates their wealth and importance. I had mapped out 15 locations prior to my trip, so the series will cover each of these. Readers of The Prince can follow along using the map included in the book. I ended up using nearly all of the locations in some way, whether as an actual location for a scene in the story, or to inform something else.

Kanturk Castle was my first stop after arriving in Shannon. The structure inspired my vision for Castle Glencurragh, a fictitious castle near Skibbereen, County Cork, which is the dream and ambition of the protagonist.

Kanturk Castle was my first stop after arriving in Shannon. The structure inspired my vision for Castle Glencurragh, a fictitious castle near Skibbereen, County Cork, which is the dream and ambition of the protagonist.

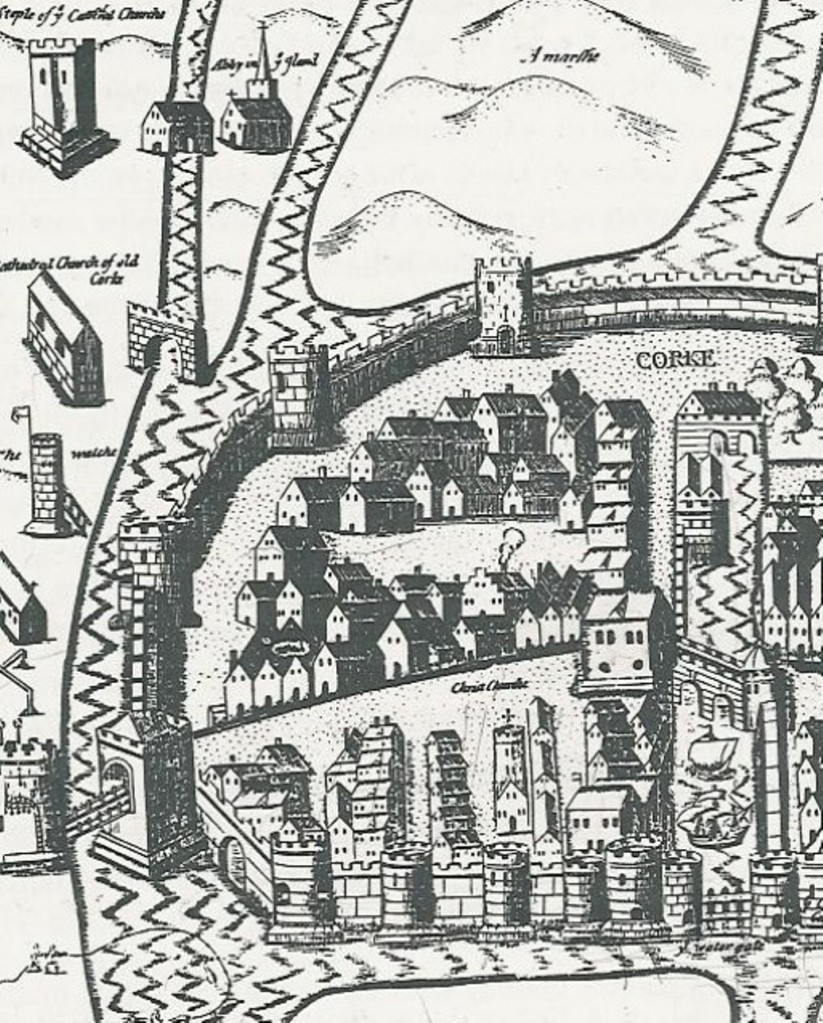

Kanturk Castle is situated in north County Cork, just off the N72 about nine miles west of Mallow, along the Dalua river, a tributary of the Blackwater. It is named for the nearby market village Kanturk that existed centuries before the castle. While the name sounds exotic and mysterious, it actually means “the boar’s head” (from the Gaelic Ceann Tuirc).

To me, the remarkable thing about this enormous and beautiful fortified manor house, and why I felt compelled to see it, is that it was the envy of all who saw it during construction, and yet it was never completed.

To me, the remarkable thing about this enormous and beautiful fortified manor house, and why I felt compelled to see it, is that it was the envy of all who saw it during construction, and yet it was never completed.

Built by Dermot McDonagh MacCarthy starting around 1609, it is rectangular with corner towers standing five stories high. It is filled with magnificent fireplaces on each floor, large mullioned windows, arched doorways and a striking main entrance with Ionic columns on each side.

(For a very detailed account of the castle with far better photos than mine, please see The Irish Aesthete.)

(For a very detailed account of the castle with far better photos than mine, please see The Irish Aesthete.)

One legend about the castle is that all the stonemasons happened to be named John, and so originally the castle was known as Carrig-na-Shane-Saor (the Rock of John the Mason). Another story I came across was that during construction, MacCarthy needed free labor, so he and his men snagged travelers passing by, put them to work as slaves, and would not release them until they had worked on the castle for a year.

Why the castle was never completed remains something of a mystery. Some accounts claim that English settlers were concerned that the size and fortification of the castle signaled more rebellion from the Irish, and the Privy Council of England halted construction. MacCarthy was so incensed, he had the blue tiles on the castle roof torn away and thrown into a stream. Other accounts hold that MacCarthy simply ran out of money to continue.

When MacCarthy’s son, Dermot Oge, succeeded him, Kanturk and the lands around it were heavily mortgaged. Dermot and his own son were killed during a Cromwellian battle in 1652, and at the end of the confederate war Kanturk Manor was awarded to Sir Phillip Perceval, an English Protestant. Sir Phillip’s descendant, Sir John Perceval, was a successful parliamentarian, named Baron of Burton, County Cork, in 1715, Viscount Perceval of Kanturk in 1722, and Earl of Egmont in 1733.

And this brings me to a very personal connection to the story.

In 1932, Kanturk was donated to the National Trust by Lucy, Countess of Egmont, the widow of the 7th Earl of Egmont who was killed in a car crash in England. Her conditions were that the castle be kept as a ruin, as it was at time of hand-over. It is designated as a national monument.

When I visited, I saw a lovely, well-kept place where the locals walk their dogs, just as I often walk my dogs along a beautiful street with a beautiful name: Countess of Egmont—on an island more than 4,000 miles away.

It turns out that Sir John Perceval, the 5th Baronet of Kanturk and the 2nd Earl of Egmont, obtained a king's grant for properties in northeast Florida during a brief period around the 1770s, when Spain ceded the lands to Britain in an exchange for lands elsewhere. Amelia Island was then called Egmont Island, where the Earl and Lady Egmont owned a large indigo plantation. The island was later renamed Amelia in honor of the daughter of King George II of England.

The portrait: Catherine Perceval (née Compton), Countess of Egmont; with Charles George Perceval, 2nd Baron Arden; by James Macardell, after Thomas Hudson, mezzotint, published 1765, NPG D2382

Thanks to: History from Mr. Patrick O’Sullivan’s summary on Historic Kanturk website (Kanturk District And Community Council); Britain-Ireland-Castles.com; The Irish Aesthete; and the Amelia Island Museum of History.

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

An heiress, a castle, a fortune: what could go wrong?

The Prince of Glencurragh is available in ebook, soft cover and hard cover from online booksellers.

https://books2read.com/u/4N1Rj6

http://www.amazon.com/Prince-Glencurragh-Novel-Ireland-ebook/dp/B01GQPYQDY/