My Father, the Fortress

/How personal memory informs story

My fourth novel, When Starlings Fly as One, was completed, edited, and in production before I realized what personal experience had bubbled up to inform the story, and why I needed to tell it. The experience is not unique by any means, and so I wonder if it might stir the ashes among readers as well.

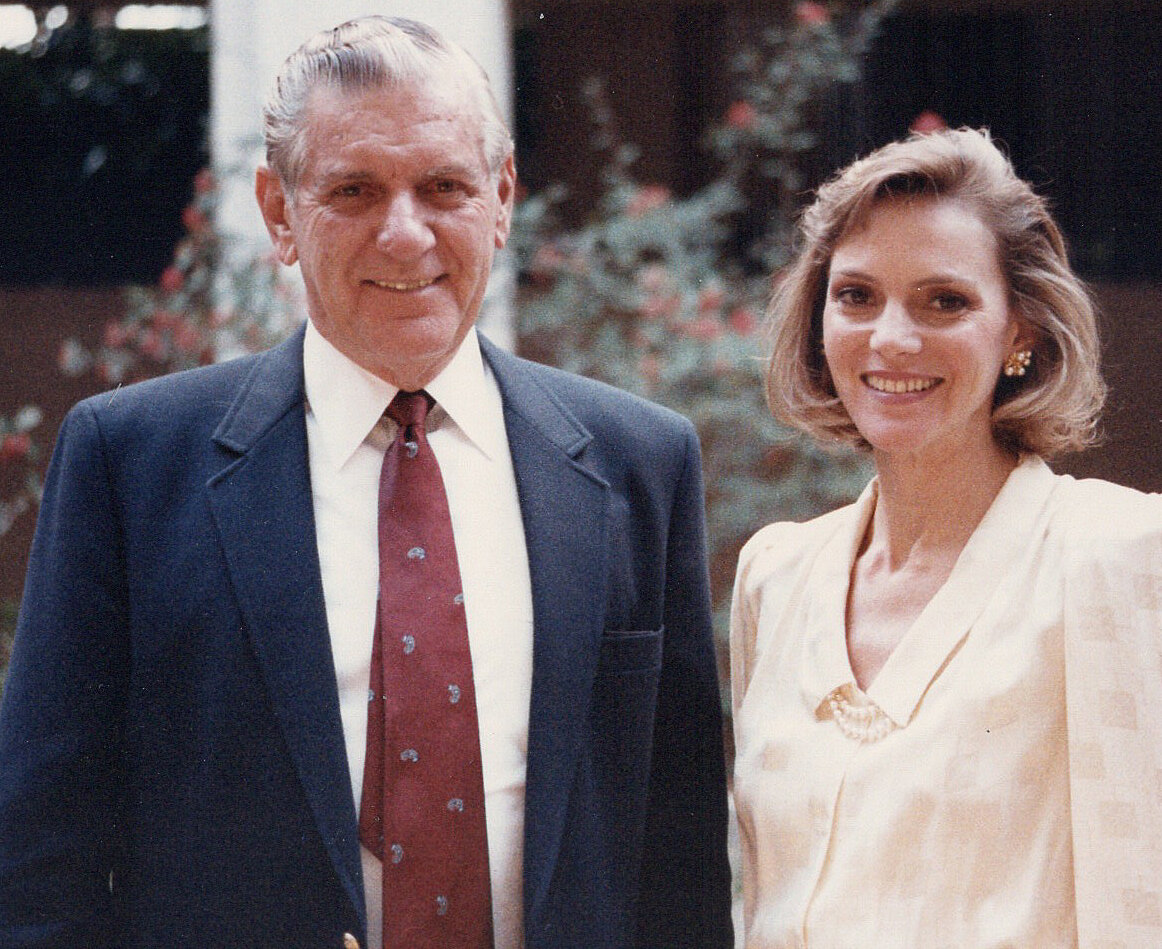

My father’s ashes were scattered in 1997 along a winding, tree-lined creek in Ireland’s County Clare. I’ll never know the exact location, having been about 7,200 miles away at the time, living in Seattle. His second wife and my niece made the long, sad journey and carried out those final wishes. After that, life carried on, and nothing was ever the same.

Like many children of the Depression Era, my father, the eldest son, had to grow up faster than he should have. Abandoned by his own father who couldn’t support his wife and four children, he had to step up to an adult role and look after his siblings while my grandmother did everything she could to succeed where her husband had failed. She ran a boarding house, raised chickens, grew a garden, cooked and cleaned, and held a job as clerk at the county courthouse.

My father drew on his mother’s strength and formed his work ethic according to her relentless standard. If he’d been a sensitive boy, as a young man he toughened, building his walls of solid material, meant to withstand the fiercest assault, the worst deprivation, the deepest insult. In time, when faced with troubling situations, he made sure that if someone had to suffer, it would always be the other guy. He was a fortress.

One day he was impressed by a wealthy man who worked as an accountant, managing other people’s money. He determined then and there his future career. All he had to do was figure out how to get it. In the navy, he learned if he performed well on a particular test, he’d be sent to college instead of to sea. He made sure he’d be among the top three scores. He went to the University of Pennsylvania and Wharton.

In similar style, when he saw a beautiful woman walking to work along a sunny street in Miami, Florida, he decided she would be his wife. He found someone who could introduce him and then he pursued her. She became my mother.

Why wouldn’t he then, build his fortress with the firm belief that he could control things and make life unfold as he planned it? But life is life, after all.

Perhaps the first fracture came when his wife delivered three girls instead of the three boys he’d intended. But princesses have their value, too, and he would never abandon his children as his father had done.

For we three daughters, it wasn’t easy living within those fortress walls. We lived comfortably, but demands for performance were sometimes unreasonable. Expectations were high, matched only by harsh criticism and humiliation. Winning his approval was supreme, but it was the smack across the side of the head that I remember most, and being invisible became the best course of action. But we also knew that inside the fortress we had a place. We would always eat. We were protected. And even if we ventured far beyond the fortress walls, if things went wrong we could return and the gates would open.

No one could have foretold what effects the new era—of sex, drugs and rock-and-roll—would have against that fortress, finding cracks in its outer walls, and seeping into the safest chambers to change thinking, shift desires, alter the paths of lives. There was rebellion inside and out. The great fortress walls began to crumble, the towers to shift. The gate didn’t lock anymore. Some unexpected things came in. Other things that had once been good went out.

All of these experiences colored in some way my telling the story of Ireland’s longest siege at Rathbarry Castle. No one expected the siege. Good things are lost, there are unexpected arrivals, there are many kinds of rebellion, along with moments of brilliance and foolishness. Transformation.

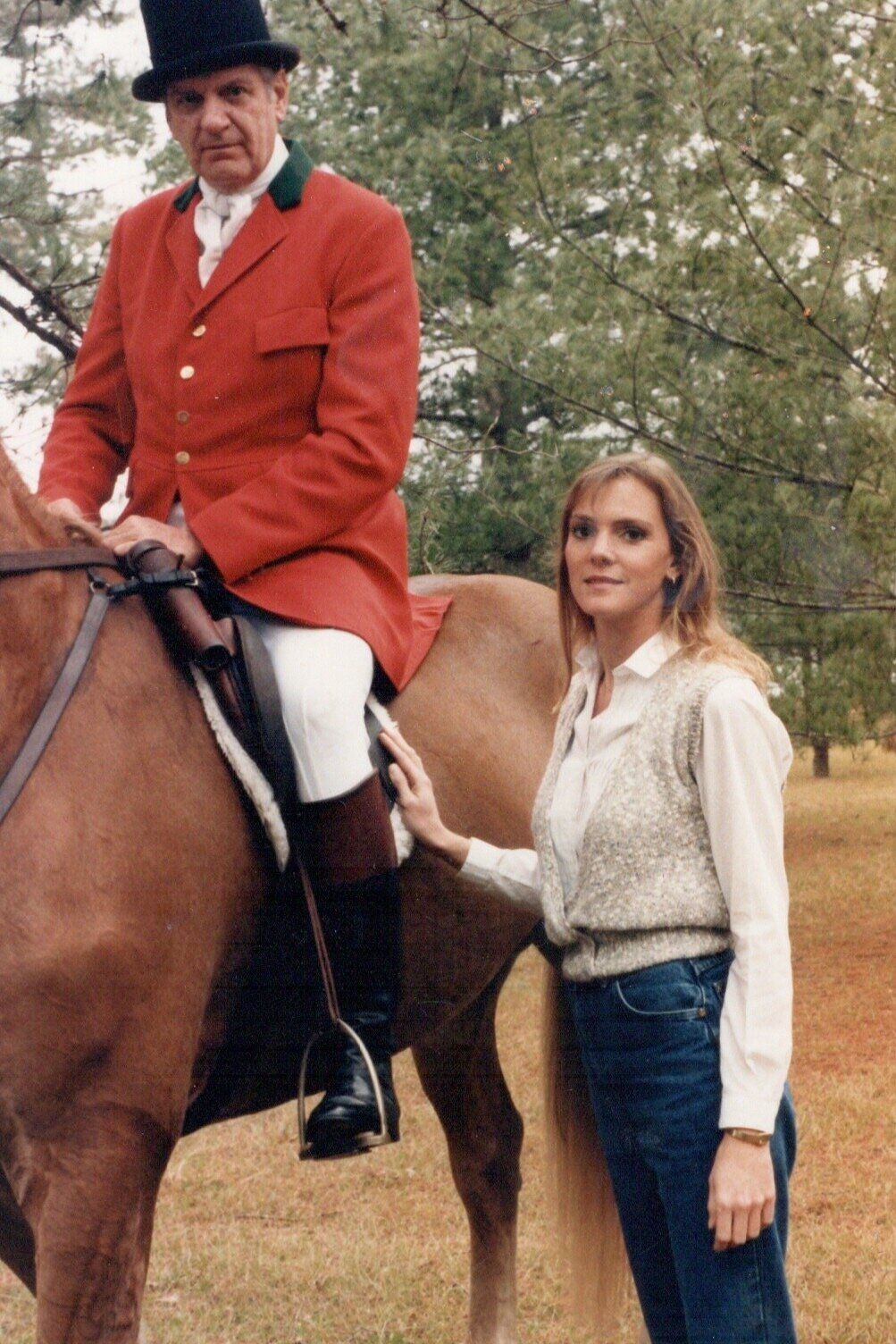

My father became like the tall, standing tower that remains amid a castle ruin: still majestic and proud, but with nothing left to guard or protect except himself. He softened, not quite returning to the sensitive boy, but taking his enjoyments quietly, his disappointments with a shrug, no longer firing from the battlements. At night he would go to an Irish pub and sing Danny Boy, a song of a parent wishing for return of a son from war; a song that, in the words of journalist Maddy Shaw Roberts, “deeply cries for home.”

I didn’t expect that after more than two decades since my father’s death, grief still rises. And what better way should it come than in story? I, like the protagonist, return to the fortress even though I know it can never be what it once was. I can’t fix it. But I can take the stone and rubble that remains, dust off a few bits to see what they can tell me, sweep out the darkest corners, and craft something of my own. I think my sisters and I have each, in our own way, made our father proud.